“When the Lord first spoke to Hosea, the Lord said to Hosea, ‘Go, get yourself a promiscuous wife and children of promiscuity… so he went and married Gomer daughter of Didlaim. She conceived and bore him a son…” (Hosea 1:2-3)

So begins a description of Hosea’s marriage with Gomer. As the Lord instructs, the prophet names the three children she gives birth to as “Jezreel” (“for I will soon punish the house of Jehu [aka Israel] for the bloody deeds at Jezreel”), “Not Accepted,” and finally “Not My People.” Gomer gets the idea–her husband does not accept her or her children.

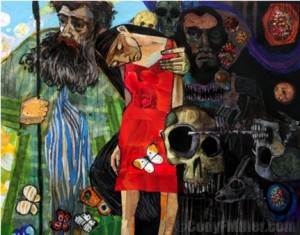

She leaves and finds protection with other lovers whom she holds in esteem. Hosea then threatens to strip his wife naked and to kill her with thirst, starve her and leave her isolated in the wilderness. He even threatens to abuse her children because of their association with their mother. Then the husband imagines in 2:14 that he will lure his wife into the wilderness and talk sweetly to her in an effort to win her back. After his earlier threat to strip her naked and leave her in the wilderness, I find his attempt at romance scary. This sudden change of tone reminds me of what counselors identify as a typical pattern of an abusive husband who, after a period of renewed tenderness, will return to his abusive ways.

Traditional commentators have deflected the prophet’s harsh language about his wife by assuming she was a harlot and therefore deserving of the verbal abuse. “The text never calls Gomer a zona (prostitute); she is a ‘wife (or woman) of harlotry,’ eset zenunim, a nebulous term unique to Hosea, which does not connote professional prostitution” (Leith, p.97). If she is not a common whore then it is assumed that she was a hierodule, a “sacred prostitute” involved sexually in foreign pagan cults. Current scholarship does not find a pervasive use of sacred prostitution in ancient Israel or Mesopotamia. “The scholarly assumption that sexual rituals were a prominent feature of Canaanite religion… can be nowhere independently substantiated” (Keefe, p.78). See my article about Tamar for a fuller discussion.

The behavior of harlots was tolerated by male society because they were not the property of a husband or father and therefore they were not threatening to the social order. Since Gomer belonged to Hosea, her dalliance with other lovers made her an adulterer who could by law be stoned to death. Whether or not Gomer was a prostitute of any kind, there is much debate among commentators whether this metaphor of adultery is a critique of fertility goddess worship, the ecological rape of the land or the male elite’s running after wealth and foreign powers. Each interpretation has its hermetical uses and should not be dismissed.

Rather than focus on why Hosea thought it appropriate to threaten Gomer, I want to pay attention to how we are to come to terms with the divine as described by Hosea. Whatever his excuse, the result is that we have a clear case of domestic abuse seemingly condoned by God (Graetz, “God is to Israel” p.131).

Even if we accept that Hosea’s marriage is “only a metaphorical, allegorical vision, that does not mean that such metaphoric imagery has no power, no force. As many have pointed out, it is no longer possible to argue that a metaphor is less for being a metaphor. On the contrary metaphor has power over people’s minds and hearts” (Graetz, “God is to Israel” p.13).

As I consider my options as a reader, I begin to wonder whether there is another side to the story. “The feminist critique of [Hosea 2:4-17] is by now well established: that it robs the woman of her voice and her point of view, that it objectifies and degrades her” (Landy, p.146). Therefore, for the sake of understanding the text, I am giving Gomer a voice when I imagine that she sits down with Hosea to discuss their marital-theological issues.

Hosea: I had to do something unexpected to get my message out there (Fontaine, Hosea p.51). I only said what God told me to for the sake of argument. God has done this before: Isaiah was required to walk naked in the street, Jeremiah could never marry or attend a funeral. Ezekiel was told not to mourn his wife’s death and Isaiah also gave his children symbolic names to herald future events. My outburst was a poetic device for discussing social anarchy (Weems, pp.1-2). Despite my strong language, I was denouncing the immorality of the ruling elite and calling to attention their political greed and egregious national policies (Weems, pp.9-10).

Gomer: Only other men could identify with your outrage and could possibly perceive your reactions as plausible and legitimate (Weems, p.41). Perhaps buying my body to teach Israel a lesson, thinking our marriage is just an allegory, and using our children as props rather than acknowledging them as real– perhaps this helps you deal with your own aversion to your threats and the state we are in (Sakenfeld, p.94). What in the image of a humiliated woman and abused children have to do with God’s love for a people? (Weems, p.1) How can you advocate repentance with obscene words?

Hosea: The sexual imagery proved suitable to express the chaos and dishonor that was sure to descend upon Israel, just as chaos and dishonor followed me when you failed to conduct yourself properly (Weems, p.32). I am the true victim here for being driven to extreme measures because you have again and again dishonored me just as Israel has shamed God. I was acting well within my rights as a husband. If God’s covenant with Israel is like a marriage then a husband’s physical punishment of his wife is as warranted as God’s punishment of Israel (McFage).

Gomer: This is self-serving lore to justify your need to control and punish women (Weems, p. 42). You are just trying to exonerate yourself and God for any appearance of being harsh, cruel and vindictive (Weems, p.19). How do you justify threatening to leave me naked and starving in the wilderness?

Hosea: When God decided to espouse Israel forever, it was so that the people would “know” only God. When I decided to marry you, it was so that you would know that only through an intimate, meaningful relationship can God be known (Weems, p.33). If Israel wants to know more than just God, and if you want to take the fruit from the tree again, then you must be expelled from the Garden of Eden, stripped naked and left as on the day you were created (Graetz, Unlocking, p.77).

Gomer: Both you and God are accessible but only on your own terms (Graetz, “Unlocking” p.77). You married me on purpose because of my promiscuity not in spite of it. So what if I did have more than one partner. Stop whining. You knew what I was like when you married me. You are just afraid of my sexual independence (Fontaine, A Response, pp. 62-3). After the way you dismissed the children and me I ran away in protest. Satisfying my own needs was a statement that my sexuality belongs to me. I challenge the belief that a wife is to be exclusively sexually devoted to her husband who has no such restriction. I am not dangerous and in need of a man’s control. Now I am in charge of my own fertility and sexuality (Sherwood, pp.120-1). I make my own choice of partners not for the benefit of a husband or his good reputation but for the satisfaction of my own desires on my own terms (Streete, p.15). Remember my name means “fulfilled”!

Hosea: Regardless of your name, your soul is at great risk! Are you sure that your persistent pursuit of other lovers is not a hollow protest? Is life really only about satisfying your own needs? What if marriage is staying together not just for selfish reasons? With true commitment we weather the storms of life together, instead of fleeing at the first dissatisfaction. Where is the love and comfort in transitory relationships? Deep down, it this really who you want to be? I forgave you. It was illegal to take you back (Deut. 24:1-4; cf. Jer. 2:1) but I brought you to the wilderness anyway bearing gifts and whispering sweet words to you. No matter how bad things get in a marriage, there is always the possibility of forgiveness and a happily-ever-after. In the same way, God loves us so much that after punishing us, the Almighty will forgive us and reunite with us.

Gomer: It’s a lovely portrait but what is the cost of believing that message after a profound breach in trust? How can domestic abuse be redeemed through romance, seduction and courtship? That such violence passes for love is a “telling commentary on societies in which domestic violence against women and children is so customary that it has attained the status of unexamined norm” (Fontaine, A Response, p. 64). I didn’t consent to any of this. There was no discussion. You are just proving yourself to be superior to your “depraved” wife by taking me back when you could have stoned me (Weems, p.32).

Hosea: I am only suggesting that it is possible to recover love, romance and intimacy in relationships that were once torn apart (Weems, p.9).

Gomer: To you and God, marriage means forever even if it doesn’t work out. I feel trapped in this marriage (Graetz, Unlocking, p.80). You have made a terrible assumption that God’s people must suffer in order to be entitled to a loving relationship. However provocative, enthralling, and entertaining your words are, as a listener I have the right to reject provocations that diminish my humanity (Weems, p. 104).

Hosea: Help me then to name the power in the world that terrifies and overwhelms me (Plaskow, p.90). How can I repair the rupture between us when I am so afraid?

Gomer: Start by realizing that your words and actions have consequences. Take responsibility for what you have threatened. As long as women continue to be brutalized, the metaphor of a battered wife should be challenged. Find an ethical model for forgiveness. I will only think of risking love again when there is no threat of violence.

Just like a couple recovering from an abusive relationship, you too get to decide whether to “throw in the towel” or work out a meaningful understanding of Hosea’s marriage metaphor. What would it take for you to feel emotionally safe with this passage?

“What to do with these texts?… what does it do to those who have been actually raped and battered, who live daily with the threat of being raped and battered, to read sacred texts that justify rape and luxuriate obscenely in every detail of a woman’s humiliation and battery? Moreover, what did it do to ancient Hebrew women to hear and be subjected to such ranting of prophets in the squares and marketplaces?” (Weems, p.8)

We can speculate that some ancient women heard the prophet on the street corner raving about punishing his promiscuous wife and walked briskly past. Are we to walk away from these texts or return to the metaphor and shout back at the prophet thereby undermining the metaphor’s hold on our imagination? “All of this only underscores the fact that reading is not the passive, private, neutral experience that we have previously believed. To read is to be prepared in many respects to fight defensively… reading does not mean simply surrendering oneself totally to the literary strategies and imaginative worlds of narrators” (Weems, p.101). And if you think that a prophet’s words from another millennium are irrelevant today, look around at the way women are depicted in headlines, billboards, commercials, advertisements, magazine covers, and the lyrics to our songs. We have a lot to grapple with the objectification of women and their pervasive abuse in our society.

For Further Reading

Bird, Phyllis A. – “‘To Play the Harlot’: An Inquiry into an Old Testament Metaphor’ in Gender and Difference, Peggy Day, ed. (Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 1989)

Brenner, Athalya, ed. – “Introduction” in A Feminist Companion to the Latter Prophets. Feminist Companion to the Bible 8. Althalya Brenner, ed. (Sheffield, Eng: Sheffield Academic Press, 1995)

Brenner, Athalya – “Pornoprophetics Revisited: Some Additional Reflections” Journal for the Study of the Old Testament 70 (1996) 63-86.

Fontaine, Carole R. – “Hosea” in A Feminist Companion to the Latter Prophets. Feminist Companion to the Bible 8. Althalya Brenner, ed. (Sheffield, Eng: Sheffield Academic Press, 1995)

Fontaine, Carole R. – “A Response to ‘Hosea'” in A Feminist Companion to the Latter Prophets. Feminist Companion to the Bible 8. Althalya Brenner, ed. (Sheffield, Eng: Sheffield Academic Press, 1995)

Frymer-Kensky, T. – In the Wake of the Goddesses: Women, Culture, and the Biblical Transformation of Pagan Myth (New York: Fawcett Columbine, 1992)

Graetz, Naomi – “God is to Israel as Husband is to Wife,” n A Feminist Companion to the Latter Prophets. Feminist Companion to the Bible 8. Althalya Brenner, ed. (Sheffield, Eng: Sheffield Academic Press, 1995)

Graetz, Naomi – Unlocking the Garden: A Feminist Jewish Look at the Bible, Midrash and God (Gorgias Press, 2004)

Keefe, Alice A. – “The Female Body, the Body Politic and the Land: a Sociopolitical Reading of Hosea 1-2,” in A Feminist Companion to the Latter Prophets. Feminist Companion to the Bible 8. Althalya Brenner, ed. (Sheffield, Eng: Sheffield Academic Press, 1995)

Lakoff, G. and M. Turner – More than Cool Reason: A Field Guide to Poetic Metaphor (University Of Chicago Press, 1989)

Landy, Francis – “Fantasy and the Displacement of Pleasure: Hosea 2.4-17,” in A Feminist Companion to the Latter Prophets. Feminist Companion to the Bible 8. Althalya Brenner, ed. (Sheffield, Eng: Sheffield Academic Press, 1995)

Leith, Mary Joan Winn – “Verse and Reverse: the Transformation of the Woman, Israel, in Hosea 1-3,” in Gender and Difference, Peggy Day, ed. (Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 1989)

McFague, S. – Metaphorical Theology: Models of God in Religious Language (Fortress Press, 1982)

Plaskow, Judith – “Facing the Ambiguity of God,” Tikkun 6/5 (1993) 70-1.

Sakenfeld, Katharine Doob – Just Wives: Stories of Power & Survival in the Old Testament & Today (Louisville: Westminster Jon Knox, 2003)

Setel, T. Drorah – “Prophets and Pornography: Female Sexual Imagery in Hosea,” in Feminist Interpretation of the Bible, Letty M. Russell, ed. (Philadelphia: Westminster, 1985) 86-95.

Sherwood, Yvonne – “Boxing Gomer: Controlling the Deviant Woman in Hosea 1-3,” in A Feminist Companion to the Latter Prophets. Feminist Companion to the Bible 8. Althalya Brenner, ed. (Sheffield, Eng: Sheffield Academic Press, 1995)

Streete, Gail Corrington – The Strange Woman: Power and Sex in the Bible (Louisville: Westminster John Knox, 1997)

Weems, Renita J. – Battered Love: Marriage, Sex, and Violence in the Hebrew Prophets. Overtures to Biblical Theology. (Minneapolis: Fortress, 1995)

Westenholz, Joan G. – “Tamar, Qedesa, Qadistu and Sacred Prostitution in Mesopotamia” Harvard Theological Review 82.3 (1989) 245-65.

Yee, Gale A. – “Gomer” in Carol Meyers, Toni Craven and Ross S. Kraemer, eds., Women in Scripture: A Dictionary of Named and Unnamed Women in the Hebrew Bible, The Apocryphal/Deuterocanonical Books, and the New Testament (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 2000)

Yee, Gale A. – “Hosea” in The Women’s Bible Commentary, Carol A. Newsom and Sharon H. Ringe, eds. (Louisville, KY: Westminster/John Knox Press, 1992)

Yee, Gale A. – Poor Banished Children of Eve: Woman as Evil in the Hebrew Bible (Minneapolis: Fortress, 2003)