Her Name

Miriam enters the Bible without genealogy, an annunciation scene or a naming ceremony. She isn’t even named. She’s just the sister of Moses. Not until she was an old woman do we learn that Moses’ and Aaron’s sister was named Miriam. Most commentaries will tell you that her name means “bitter water” based on the rabbinical understanding that her name is derived from the Hebrew root mrr, to be bitter.

“This derivation, however, is unlikely since the particular form of Miriam’s name does not represent any known form of this root in the Hebrew…It appears most probable that the name is to be traced to a form of the Egyptian mer, ‘love.’ The Egyptian form, mry(t) (‘the beloved’) is commonly found in Egyptian records in combination with the name of a deity, e.g., mry(t) pth (‘Beloved of Ptah’)…” (Burns, p.9).

Therefore, the best explanation for the origin of Miriam’s name is that it is derived from an Egyptian word meaning “beloved,” a common component in Egyptian names. If this is the case, the biblical narrator dropped the name of the god that would have been attached to her name.

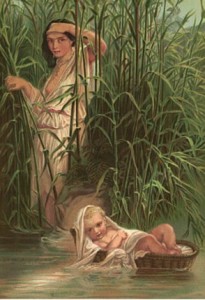

Miriam and Baby Moses

As I mentioned in my article about the Pharaoh’s daughter, we first encounter what we presume to be Miriam at the riverbank following the path of Moses’ woven ark. Once the princess discovered the crying child, Miriam initiated a conversation. “Shall I go and summon a wet nurse from among the Hebrews that she might nurse the child for you?” We learn that Miriam was a bold child who spoke with the power of persuasion, encouraging the king’s daughter to adopt the child even before she had indicated any desire to be a mother of the forbidden Hebrew child. We can make up lots of reasons why Pharaoh’s daughter might have wanted to disobey the decrees of her father, but regardless of her back story, it is clear that Miriam and the princess became cohorts in a rebellion that began with the rescue of Moses.

Miriam the Prophetess

“Then Miriam the prophetess, Aaron’s sister…” (Exodus 15:20)

We next encounter Miriam about 40 years later at the edge of the Reed Sea. Here we learn that she was considered a prophetess, a title she received long before Moses obtained the same designation. Gafney has conducted a thorough research of the role of women prophets in the Bible and finds Miriam’s song and dance to be a manifestation of her prophetic activities. Like the prophetess Deborah, Miriam appears to have been an ecstatic prophet since her oracles were delivered through song and dance.

“Musical performances, particularly when accompanied by percussive instruments, are identified as prophetic performances in 1 Samuel 10 and 1 Chronicles 25…As a prophet, Miriam conducts the first religious musical performance in post-Exodus Israel; it is characterized by an exhortation to worship through song, charismatic singing and dancing led by women playing tuppim, hand drums” (Gafney, p.80).

Burns questions whether Miriam’s musical and dance performance was used for the purposes of evoking ecstasy in the manner of the prophets of 1 Sam. 10:5ff. and 1 Kings 18:26ff.

She writes that the “song of Exod 15:21 bears the formal characteristics of a hymn and not those of an oracle. Miriam leads the community in a proclamation of faith and this, of course, differs significantly from delivering the Lord’s word to the community. She does not speak regarding the outcome of a forthcoming battle but rather articulates the religious dimension of a past victory” (Burns, pp.46-7).

Since none of her actual prophecies were preserved and Miriam is not described as prophesying, Burns deduces that the title of prophetess was tacked on later to honor her. There are a number of prophets mentioned in the Bible without recorded oracles and their legitimacy as prophets is never questioned. Therefore, the lack of written texts recording her oracles is a false litmus test for identifying Miriam’s role. The scattered references to Miriam throughout the Hebrew Bible leave us with the impression that her role was far greater than what has been handed down to us. A number of books are mentioned in the Bible which have not survived such as the Book of Yashar, the Book of the Battles of Yahweh and the Chronicles of the Kings of Judea. From this we learn that it would be presumptuous to think that nothing else was recorded about Miriam, including her prophetic utterances.

After a careful analysis of all the texts which mention Miriam, Burns concludes that she was a “mediator of divine will” but in the priestly tradition, not prophetic.

The “celebration which she led was essentially a cultic one. That this is so is suggested by the fact that the victor at the sea was Israel’s Divine Warrior and not a human one. The essentially cultic nature of Miriam’s celebration is confirmed by an examination of the use of dance and song in other cultic victory celebrations” (Burns, pp.11-12).

Whether Miriam’s authority lay within priestly or prophetic traditions puts too fine a point on the matter. There is evidence that these roles were not considered distinct until later in Israel’s history. Certainly we can agree that she officiated at a “celebration of the foundational event of [the] Hebrew religion” (p.121) and was a cultic authority instrumental in the redemption of the Israelite community.

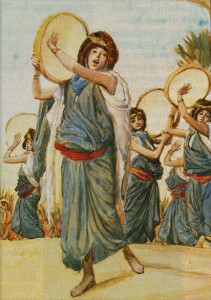

Miriam, Drums and Dance

Artwork by James TissotThen Miriam the prophetess…took a drum [התף] in her hand, and all the women went out after her in dance with drums [בתפים]. (Exodus 15:20)

In artistic representations Miriam is most often depicted as singing at the edge of the sea with a drum in hand, leading the women in dance. Yet Miriam’s role goes beyond a simple joyful celebration of freedom. It is precisely in her act as a musician that she is named a prophetess (Schwartz, Introduction, p.5). Specifically, Miriam performed a victory dance-song, a celebration honoring the returning warrior carried out exclusively by women.

Oesterly writes, “There are some grounds for believing that the custom of which the Old Testament speaks was a remnant of what was originally a dance performed by women which had for its object the helping of the men to gain a victory by means of imitative magic. In the Old Testament there is, of course, no trace of this beyond the fact that the dance was performed by women” (pp.40-41).

Based on the use of the victory dance throughout the Hebrew Bible, it appears to be a dramatic representation of God’s victory over Israel’s enemies.

Throughout the Iron Age Levant, Archaeologists have found small terracotta figures of women holding disks in their arms. Meyers has amply demonstrated that these figurines are depictions of ordinary women playing tuppim, hand-drums. Most English translations render tuppim as tambourines or timbrels, but these instruments did not appear before the thirteenth century C.E. Traditionally women in the ancient Near East led the communal songs with drumming and dancing. “Just as virtually all the terracottas of hand-drummers depict females, so too the biblical references to membranophone-playing exhibit a distinct connection with women” (Meyers, Miriam, p.220). Sociological and ethnographic studies have concluded that women who have access to female groups, such as a drum ensemble, enjoy greater status within the overall community.

“The leaders and/or members of the community of ancient Israel who expected female ensembles to validate their victories in an artistic form and who watched their performance were thereby acknowledging the expertise of the women as well as their essential part in concluding the series of events that constituted victorious warfare” (Meyers, Miriam, p.228).

Being prepared to compose and perform the victory war dance required a level of competence only acquired by participating in a professional women’s association for purposes of rehearsal and perfection of their craft.

The festival in honor of the Divine Warrior recorded in Isaiah 30:29-32 envisions specific dance moves and musical responses for the participants: “And every stroke of the staff of punishment which the Lord lays upon them will be the sound of drums and lyres; battling with brandished arm he will fight them.” Accompanied by the musicians, the women appear to have danced with violent movements. Burns suggests that the victory celebrations involve consecrated dances integral to the Miriamic cultic tradition. The “dance is not merely an aesthetic pursuit existing side by side with other practical activities. It is the service of the god, and generates power: the rhythm of movement has a compelling force…In the dance life is ordered to some powerful rhythm and reverts to its primeval motion” (van der Leeuw, p. 374). The dance of Ex. 15:20 was a ritual action insuring that Yahweh would continue to provide victory in battle.

Song of the Sea, Moses’ Song or Miriam’s Song?

“And Miriam chanted for them: Sing to the Lord, for He has triumphed gloriously; Horse and driver He has hurled into the sea.” (Exodus 15:21)

Ex. 15:1-18 records the song the Israelites sang at the Reed Sea. It is one of the oldest texts in the Bible and has become know as the “Song of the Sea.” Then in Ex. 15:21 Miriam sings a couplet almost identical to the beginning of the previous song. For over 100 years scholars have debated whether Moses or Miriam should be credited with the longer hymn and whether the shorter version predated the lengthier version. There are two main opinions regarding the dating and authorship of the hymn(s):

1) The longer song in Ex. 15:1-18 is the oldest version and the shorter version in Ex. 15:21, which Miriam sang, is an abbreviation of Moses’ song.

2) The snippet we get in Ex. 15:21 is the original which was later elaborated upon to arrive at the longer version. There is evidence that the two-line war victory chant circulated independently from a longer hymn. “Thus, those who say that victory songs are originally short, two-line stanzas repeated indefinitely might well be correct…There are good reasons for regarding [Miriam’s two-line stanza] as the older of the two traditions that record the celebration” (Burns, pp. 15-16).

Most scholars have come to the conclusion that both the short and long versions of the song should be attributed to Miriam and therefore have renamed it, the “Song of Miriam.”

“The accumulated weight of literary, textual, historical, sociological, musicological, and feminist research on Exodus 15 indicates that Miriam is the more likely author. Indeed, the fact that the Song is a victory hymn, a genre associated with female rather than male musicians, in itself is a compelling enough reason to assign composition to Miriam rather than to her more famous brother” (Meyers, Exodus, p.116).

Recently a third theory has taken shape, namely that originally there existed a longer song attributed to Miriam, similar but not identical to the “Song of the Sea” which has traditionally attributed to Moses. A fragment found among the Dead Sea Scrolls (document 4Q365), contains eight lines of poetic text just after Miriam’s two-line song we are familiar with in the canon. The fragment reads:

1. you despised [or: you plundered]…

2. for the triumph of…

3. You are great, a savior…

4. the hope of the enemy perishes and he is…

5. they perished in the mighty waters, the enemy… 6. and he exalted her to their heights…you gave… 7. working a triumph.

What we learn here is that Miriam had her own song similar to but not the same as the “Song of Moses.” Although this handful of fragmented lines of Miriam’s song echoes portions of the unbroken song we have in the Hebrew Bible, it also “signals other themes, including, in the phrase ‘and he exalted her to their heights,’ an indication that God acted to save his people in part through a woman, Miriam. This ‘by the hand of a woman’ theme is a trope that turns up in other examples of the genre known as victory song” (Murphy, p.56). This trope implies that God protects the weak through the least likely of saviors, the weak themselves, thereby emphasizing God’s strength.

Some scholars see Moses’ and Miriam’s songs as being contrapuntal, responding back and forth to each other like the call and response form of southern field slave songs. Although it has been assumed that Miriam led only the women in song and Moses the men, the grammar of the songs tells us that both songs were addressed to all the people and the singers were not divided by gender.

Miriam Confronts Moses: Was Miriam Racist?

When they were in Hazeroth, Miriam and Aaron spoke against Moses because of the Cushite woman he had married: “He married a Cushite woman!” They said, “Has the Lord spoken only through Moses? Has He not spoken through us as well?” (Numbers 12:1-2) It’s easy to jump to the conclusion that by rejecting Moses’ Cushite wife, Miriam and Aaron were racist. Since God did not approve of their prejudice, many readers find the punishment of turning skin as “white as snow” for rejecting a black woman a reasonable consequence.

Recent “scholars have argued effectively against the presumption of this kind of racism in the ancient world. Further, the old notion that leprosy is a divinely inflicted punishment for sin, and the linguistic leap from ‘snow’ to ‘white,’ reflects the contemporary racial assumptions of the commentator. It cannot be overemphasized that the word ‘white,’ lavan, is not in this text” (Gafney, p.84).

In an earlier article regarding Moses’ Cushite wife, I suggested that Miriam and Aaron weren’t opposed to the color of his wife’s skin. Rather, they thought God disapproved of intermarriage with people of other nationalities. Moses’ marriage challenged his siblings’ leadership and their understanding of God’s laws. Since God sided with Moses on the matter, clearly at this stage of Israelite history, intermarriage was not forbidden. Not only did Yahweh approve of the inter-national relationship, but subsequent biblical writers never castigated Moses for his choice of wives. The objection to intermarriage became a preoccupation later in biblical history.

Traditional Jewish commentators, including Rashi, interpret this passage as a description of Miriam speaking on behalf of Moses’ wife, not against her. They state that Miriam chastised her brother for neglecting his wife. However, there is no evidence in the text to lead to this conclusion. In addition, rabbinical literature assumed that Cush was another name for Midian, the land in which Moses married Zipporah, and therefore they equate Moses’ Cushite wife with Zipporah. Most modern scholars do not find this to be a convincing argument.

Fischer explores an interesting line of thought in her article, “The Authority of Miriam.” She demonstrates that Numbers 12 was written after the exile when Persia ruled over Israel. The biblical works produced during this timeframe demonstrate a tension between those who opposed marriage to foreign women and those who insisted that mixed marriages should remain intact. Women prophets were active during this time (cf. Ezra 13; Neh. 6:14) and were probably members of the group that resisted the dissolution of mixed marriages.

“They agitate against a harsh course in matters of mixed marriages and, in their argumentation, they appeal to God’s word: Yhwh has also spoken to us! In so doing the group that is the opposition in the mixed marriage issue claims for itself the prophetically legitimate interpretation of the Torah” (p.167).

Fischer concludes that the intention of Num. 12 is not to show God’s displeasure with women in positions of leadership; rather it demonstrates the conflict between two different camps of thought about who has the authority to dictate God’s will on the issue of intermarriage.

God’s Rebuke

“The Lord heard it…The Lord came down in a pillar of cloud, stopped at the entrance of the Tent, and called out, “Aaron and Miriam!” The two of them came forward; and He said, “Hear these My words: When a prophet of the Lord arises among you, I make Myself known to him in a vision, I speak with him in a dream. Not so with My servant Moses; he is trusted throughout My household. With him I speak mouth to mouth, plainly and not in riddles, and he beholds the likeness of the Lord. How then did you not shrink from speaking against My servant Moses!” Still incensed with them, the Lord departed.” (Num. 5-8 , 12:2)

In response to Miriam and Aaron’s insistence on their own revelatory authority, God responded with a clear message that Moses’ prophetic experience preempted theirs. Ironically, while claiming that God only spoke directly to Moses, God actually spoke directly to the disgruntled siblings. “He comes, not in a dream or vision or riddle, but as the author of direct discourse. And Miriam and Aaron have no need to rely on Moses to make sense of what God has said” (Fewell/Gunn, p.115). Putting aside the puzzle of the hierarchy of prophecy, obviously God did not single out Miriam at this point as being unworthy of religious leadership. Just prior to the conflict between the siblings in Num. 11 a number of people received the spirit of prophecy (v.26) and Moses exclaimed that he wished everyone had the power of prophecy. In this context, Fischer claims that Numbers 12 does not show explicit hostility toward women in authority.

But then God punishes only Miriam with a skin disease. Is this the end of prophetic democracy? Are women being told to stay in their proper places? And if they oppose their male superiors they will pay a heavy price for their defiance?

Was Miriam Stricken with Leprosy?

“…there was Miriam stricken with scales like snow…” (Num. 12:10)

Before we deal with the ethical and theological issues associated with Miriam’s skin disease, let’s figure out what it was. In Hebrew the word usually translated as “leprosy” is sara’at [צרעת]. First off, “leprosy” (modern Hansen’s disease) did not occur in the Middle East until much later. “From the medical, historical and palaeopathological evidence it is clear that biblical ‘leprosy’ is not modern leprosy” (Hulse, p. 91). In addition, archaeological and osteoarchaeological evidence fails to demonstrate the existence of leprosy in biblical Israel.

So what was sara’at? Typically sara’at is translated as being like snow and in some cases as white as snow.

“Certainly sara’at is, in some cases, said to have an element of white about it but this is no reason for the gratuitous and misleading addition of ‘white’ to the phrase ‘as snow’. Snow has other qualities besides its whiteness and in Palestine, where snow is usually a very temporary phenomenon, the characteristic most likely to be recalled by the phrase ‘as snow’ is that snow falls as flakes” (Hulse, p.92-3).

The description of skin being like snow emphasizes the excessive peeling and flakiness of the skin rather than the color.

“The importance of peeling of the skin or desquamation in sara’at is confirmed in Aaron’s plea that Miriam’s transient ‘leprosy’ should be cured: ‘Let her not be as one dead, or whom the flesh is half consumed when he cometh out of his mother’s womb’…If an unborn infant dies at least several days before it is delivered it usually becomes ‘macerated’, that is, it undergoes a special type of decomposition…The most striking external feature of such a stillborn child is the way the superficial layers of the skin peel off” (Hulse, p.93).

Therefore, Aaron appears to be bringing attention to the flakiness characteristic of sara’at.

After a careful analysis, Hulse concludes that Miriam was stricken with psoriasis, a non-infectious condition. It leaves a trail of scales about and when the irritated skin is scratched it leaves blood marks. “It is easy to understand how a community which had acquired the concept of the clean and the unclean should regard such people as unclean” (Hulse, p.100). People with sara’at were segregated from the community not for public health reasons but because the loose, scaly skin must have appeared to belong in the same category of other unclean substances like menstrual discharges and semen.

Miriam’s Punishment

“Still incensed with them, the Lord departed. As the cloud withdrew from the Tent, there was Miriam stricken with snow-white scales…And Aaron said to Moses, “O my lord, account not to us the sin…” (Num. 12:9-11, JPS [see below for alternate translation])

In his well-titled article, “Miriam’s Challenge: Why Was Miriam Severely Punished for Challenging Moses’ Authority While Aaron Got Off Scot-Free?” Anderson summarizes the two main positions scholars have taken to explain the discrepancy in treatment between Miriam and Aaron as follows:

1) Aaron merely followed Miriam in criticizing Moses and therefore only she was punished. Coats finds evidence for this stance in v. 1 where a feminine singular verb is used when Moses is criticized for marrying the Cushite woman (p.262). This would imply that Miriam alone objected to Moses’ wife. The problem with this stance is that God held both siblings responsible for the gaffe and his anger burned against “them” equally (v.9).

2) Another tact is to assume that Aaron was originally punished along with Miriam but later redactors didn’t care for the idea of a high priest with skin disease so they changed the text. The later Jerusalem priesthood venerated Aaron as their ancestor and therefore preserved a positive portrayal of their founder. Miriam on the other hand, did not have an authoritative tradition to preserve her memory in an affirmative way (Huwiler, p. 54).

Gafney notes that in verse 11 it is possible to read that Aaron examined himself and found that he was diseased as well as his sister. “When Aaron turns, there is a repetition of the exclamation, metzora’at, disease! (The NRSV adds at the end of the verse that Aaron ‘saw that she was leprous’; the text only has ‘then and there, diseased skin,’ without specifying that Aaron saw or that Miriam was diseased.) My reading is that the second imposition of disease was on Aaron. Talmud Bavli, Shabbat 97a records that Rabbi Akiba also held this view” (Gafney, p.84). This then would be Gafney’s suggested translation of Numbers 12:10-11:

“And the cloud turned away from the tent, and then and there, Miriam was diseased like snow! And Aaron turned towards Miriam and then and there, diseased skin!” And Aaron said to Moses, ‘It is in me, my lord, please do not place on us the sin which we have been foolish and in which we have sinned.'”

The consensus among scholars is that two separate stories were woven together in this pericope. The first involved only Miriam challenging Moses’ authority and as a result she was punished with the skin disease. The second involved both Miriam and Aaron questioning Moses’ authority and if there was a punishment, it was not preserved. If the two strands are separated, and Miriam was the only one to protest, the prospect of her being singled out makes her punishment more palatable.

However, the way that the final editors have compiled this story (the text that we have been given) leaves us questioning God’s justice toward women. Those who believe that only Miriam was punished with the skin disease have used this passage to justify their opposition to the ritual roles of women in synagogues and churches. Next I will explore other approaches to this text that might offer a more egalitarian model for religious leadership.

Did Moses Cause Miriam to Become Diseased?

Gafney suggests a way to let God off the hook. What if it was Moses who punished Miriam? Notice in verse 9 that the “leprosy” is mentioned after God departed. While God was gone, Moses inflicted Miriam with the skin disease. “This reading is supported by Aaron’s first intercession in verse 11, in which the human form of adon, adoni (lord, my lord, a common form of address for human males…), is used rather than the Tetragrammaton, pointing to Moses and not YHWH as the addressee” (Gafney, p.84). In other words, Aaron turned to Moses and pleaded with his brother to take back the blight Moses had afflicted upon their sister. I find this analysis intriguing but odd. In light of the fact that Moses immediately cries out to the Lord to heal Miriam, it’s not a natural reading to assume that he had just punished his sister. And if he could curse her with a disease, why couldn’t he heal her as well?

Aaron Protests, Moses Intercedes and God Rebukes

“Let her not be as one dead, who emerges from his mother’s womb with half his flesh eaten away.” So Moses cried out to the Lord, saying, “O God, pray heal her!” But the Lord said to Moses, “If her father spat in her face, would she not bear her shame for seven days? Let her be shut out of camp for seven days, and then let her be readmitted.” (Numbers 12:12-14)

Aaron used the metaphor of a stillborn’s half eaten flesh to describe Miriam’s skin disease. Rather than focusing on the goriness, Fewell and Gunn pick up on the psychological aspect of this image. Aaron stresses a mother’s loss of her baby but God responds with a father-daughter conflict. Miriam “is not a baby lost to her mother, but a daughter whose father has spit in her face. Miriam, implies God, is not innocent, but willful…And God is no grieving mother; he is an angered father who will not tolerate insubordination–not from a ‘daughter'” (p.116). The use of female imagery adds weight to the argument that Miriam, as a woman, was singled out for special punishment. “The woman’s body suffers the brunt of divine anger, whether that anger is legitimate or not…women’s bodies, far more often than men’s, bear the punishment for insubordination” (Fewell/Gunn, p.116). Unfortunately, the Bible offers many examples of women who assert their independence then suffer the wrath of men and God.

That the issue is Miriam’s outspokenness is further confirmed by the specific disease she was punished with. For a prophet, the worst punishment for a prophet would be a skin abnormality that would prevent communication from God (Gafney, p.84). This would then link Miriam’s proclamation that God speaks through her to the specific ailment that would prevent communing with the divine.

Then to add insult to injury, Moses had to intercede with God on her behalf. This “merely underlined Miriam’s subordinate status, and that his intercession proved successful served only to emphasize the extent of his power and influence…for the only way in which she could be cured of her disease was through the mediation of the one whose intimacy with God she had just called into question” (Davies, p.65). Even if Aaron was punished with the same skin disease, the allusions to female suffering severely limits our sense of justice being meted out evenly between the siblings. As a woman reading this story, it’s hard not to come to the conclusion that the God of Numbers likes boys better than girls.

What if Miriam Was Not Punished At All?

Ok, so far Miriam (and women in general) are getting the short end of the stick in Numbers 12. Before calling into question the value of the Bible for progressive readers, I must mention a very creative attempt to redeem the text.

Years ago I read Labowitz’s book God, Sex and Women of the Bible and was blown away by her translation of the incidence at Hazeroth. Most translations depict Miriam being punished with a skin disease, as we have been discussing. However, in the original Hebrew no vowels were used. Therefore translations are educated guesses as to the meaning of each word based on the context and how the word is used throughout the corpus. Using a Hebrew lexicon and dictionary, Labowitz returned to the root consonants of the text and found new meanings for some of the key words in Miriam’s story. Since my first reading of Labowitz’s work, I have encountered several feminist commentators who interpret Miriam’s separation from the camp as a ritual designed to sanctify her as a prophetess, not as a punishment.

So let’s look at what these commentators propose with a few charts thrown in for clarification. Starting with Num. 12:9:

Traditional Translation

“And God’s anger was sparked [vayechar-aff] against them, and [God] departed [yachar]”

Literal Translation

“burned with anger God departed”

Labowitz notes that the Hebrew phrase “burned the anger,” vayechar-aff, can also mean “glowed.” The root letters of vayechar, can also be used to spell yachar, “linger.” With these adjustments the translation would be:

“God’s glow lingered.”

In other words, God was not angry with Aaron and Miriam but poured out a glowing presence. As Schwartz notes, “The interpretation of God burning with anger is up to those who perceive anger within the context of this story. This sentence just as easily reads that ‘God was kindled more within them’…The ‘kindling of God’ within Miriam seems to imply that she is receiving divine communication” (p.174). As encouraging as such an interpretation may be from a feminist perspective, elsewhere the phrase vayechar-aff appears in the Bible, it can only reasonably mean the wrath of God. Schwartz counters that this is evidence that two separate traditions, one that portrays Miriam positively and the other malevolently, have been entwined by the editor to “change the tone of the original story” (p.177).

Numbers 12:10 is the next challenging verse:

Traditional Translation

As the cloud withdrew [sar] from the tent, there was Miriam stricken with zora’at! When Aaron turned toward Miriam, he saw that she was stricken with zora’at.

Literal Translation

“the cloud had withdrawn over the tent behold Miriam zora’at turned Aaron toward Miriam behold she zora’at”

In this verse Labowitz remarks that sar, “withdrew” could also mean “to draw near and around” something and zora’at can also mean “smitten, overtaken, overwhelmed.” The sentence would then read:

“And the cloud [of God] drew near around the tent, and Miriam was smitten and became as snow; and Aaron turned to Miriam, and behold, she was smitten.”

Labowitz concludes that “Miriam was overtaken in a spiritual epiphany, and her skin became white as snow because she had just seen and touched the likeness of God and felt overwhelmed” (p.157). Note that this same term, zora’at is used in Exodus 4:6 when Moses first spoke to Yahweh and is called to return to Egypt to free the Hebrew people. Moses asked God how the people would know that he is acting with divine authority. God made Moses’ hand become zora’at as snow, the same phrase used to describe Miriam’s skin.

“God chooses a physical sign, a transformation of [Moses’] skin’s outward appearance, as a symbol of divine communication. God chooses tzara’at [zora’at]. When Moses’ hand turns white [sic] with leprosy [sic], God is not punishing him, but choosing him for a special purpose…Why should it be impossible to believe that Miriam’s tzara’at serves a similar purpose?” (Schwartz, If There Be, p.173).

Leviticus 13:13 states that if a person’s whole body becomes white from zora’at then the person is to be declared ritually clean. This coupled with the image of the purity of snow, leads me to think that it was possible that having the condition of zora’at was a holy condition. Her later seclusion from the Israelite camp would then be a period of consecration like the seven days of separation for purification required by Aaron and his sons at their inauguration as priests (Lev. 8).

In verse 12 Labowitz does not provide a positive spin for Aaron’s comparison between Miriam’s skin and to that of a stillborn. Schwartz, however, sees Aaron’s plea that Miriam “not be like one from the mother’s womb” as a continuation of the motif of childbirth repeated throughout the exodus story.

“Midwifery, deliverance, care for born and unborn generations; these are the overarching themes of Miriam’s life…By using the childbirth metaphor, Aaron recognizes Miriam’s role as spiritual, if not literal, midwife to the Hebrews” (p.175).

I’m not sure I am convinced of this argument since the description of the stillbirth as one “who’s flesh is half eaten away” does not connote an affirmative interaction between the divinity and the siblings.

But let us carry on to the next “pleasant” comment in Num. 12:14.

Traditional Translation

“But the Lord said to Moses, ‘If her father spat [yarok] in her face, would she hide [ha-lo tikkalem] her shame for seven days? Let her be shut out of camp for seven days, and then let her be readmitted.”

Literal Translation

“said the Lord to Moses, her father spit , spit her face not bear seven days close up. Seven days out of the camp and afterward may be received.”

According to Labowitz, in this verse we learn that the root consonants of yarok can mean “a green plant” or “a bud that flourishes within itself” and the roots of ha-lo tikkalem can mean, “she will complete.” Therefore Labowitz translation would be:

“God said to Moses, ‘I will bring the bud that flourishes within her to completeness within seven days; she will retreat outside the camp and then she will rejoin you.'”

In other words, Miriam blossomed after her sacred encounter with God. Labowitz concludes that retranslating “Miriam’s story elevates her from rebuked gossip to prophetess” (p.171). This positive interpretation does not account for God’s elevation of Moses’ relationship to the deity above his siblings or the later Deuteronomistic writers interpretation of Miriam’s disease as a punishment, for example Deut. 24:8-9 (“In cases of a skin affection be most careful to do exactly as the levitical priests instruct you. Take care to do as I have commanded them. Remember what the Lord your God did to Miriam on the journey after you left Egypt”).

Although from a scholarly perspective this reinterpretation of the text has some problems, I find it thought provoking and liberating. If the rabbinical tradition can interpret Miriam’s criticism as a rebuke against Moses’ sexual and emotional neglect of Zipporah, what prevents modern readers from retranslating the text to suit a more encouraging view of Miriam in Numbers 12? The text certainly challenges us to wrestle with the God of the Hebrew Bible. What “positions” are legal on the mat of biblical interpretation? Or is it no holds barred?

Loyalty to Miriam

“So Miriam was shut out of camp seven days: and the people did not march on until Miriam was readmitted.” (Numbers 12:15)

In spite of the conundrum of Miriam’s punishment, it is clear that she remained an important and powerful figure in Israel’s historical memory. In later prophetic literature God speaks through Micah:

“For I brought you up from the land of Egypt, and redeemed you from the house of bondage; and I sent before you Moses, Aaron and Miriam.” (Micah 6:4)

This portrait of Miriam emphasizes her not only as a leader in the early Israelite community but also establishes that she was a divinely commissioned authority (Burns, p.111). Burns also demonstrates that the full endorsement of Miriam as a leader of the Israelite community was an early tradition and not a late innovation by later writers. Though Numbers 12 raises questions about a hierarchy of leadership between Miriam and her brothers, the story does not deny her claim to having access to divine communication.

As I discussed elsewhere regarding Miriam’s death, Miriam was firmly connected with cultic activities at the oasis of Kadesh in the wilderness. Von Rad notes that “Kadesh was…a well-known sanctuary where divine justice was administered and cases in dispute decided” (vol. 1, p.12). Kadesh was known as the “Spring of Judgment” (Gen. 14:7) and it is plausible that divine verdicts were sought and received as part of the Kadesh religion (Sheehan, pp. 27-29). Together with Miriam’s association with the cult at Kadesh and her role as a leader of the Israelites, Miriam might have been the leader of the judgment cult at the Kadesh shrine. “Numbers 12, then, might well reflect an ancient memory of Miriam’s role in voicing divine decisions in the cult of Kadesh” (Burns, p.127). Simpson suggests that the confrontation described in Numbers 12 might reflect an ancient antagonism between Kadesh authorities represented by Miriam and the Mosaic tradition (p.430). There is strong evidence in the latest biblical research that Miriam had a substantial following of religious devotees to her brand of “religion.” Most agree that the Miriamic narrative is the older, original narrative.

Miriam is mentioned again in 1 Chronicles 5:29, indicating that she remained active in the historical imagination of Israel. In fact, a catalog of the references to Miriam throughout the Hebrew Bible span the entire period of canonical composition. “From earliest times until the latest, biblical writers included her as a figure from their ancient past whose memory was valued” (Burns, p.129). Despite any efforts to suppress a “Miriamic tradition” a surprising number of clues seem to have been left behind indicating that she was an authentic religious figure in our ancient past.

Finally I want to bring your attention to an allusion to Miriam in the Book of Jeremiah. He envisions the restoration of defeated Israel by recalling Miriam at the Reed Sea: “Again I will build you, and you will be built, O virgin Israel! Again you will adorn yourself with drums, and will go forth in the dance of the merrymakers” (31:4). In the bright future, Miriam and Israel will be returned to their rightful place and again lead with song and dance. Perhaps the time has come to take up the Miriamic tradition and dance once again with drums!

For more information, see Miriam’s Death.

For Further Reading

Ackerman, Susan – “Why is Miriam also among the Prophets? (And is Zipporah among the Priests?)” Journal of Biblical Literature 121 (2002), 47-80.

Anderson, Bernhard W. – “Miriam’s Challenge; Why Was Miriam Severely Punished for Challenging Moses’ Authority While Aaron Got Off Scot-Free?” Bible Review 10 (1994): 16, 55

Brooke, George J. – “A Long-Lost Song of Miriam,” Biblical Archaeology Review 20/3 (1994), 62-65.

Burns, Rita J. – Has the Lord Indeed Spoken Only Through Moses? A Study of the Biblical Portrait of Miriam. SBL Dissertation Series 84 (Atlanta, GE: Scholars Press, 1987)

Coats, George W. – Rebellion in the Wilderness: The Murmuring Motif in the Wilderness Traditions of the Old Testament (Nashville: Abingdon Press, 1968).

Cross, F.M. and D.N. Freedman – “The Song of Miriam” Journal of Near Eastern Studies, 14 (1955) 237-250.

Davies, Eryl W. – The Dissenting Reader: Feminist Approaches to the Hebrew Bible (Aldershot, Eng.: Ashgate, 2003)

Fewell, Danna Nolan and David M. Gunn – Gender, Power, and Promise: The Subject of the Bible’s First Story (Nashville: Abingdon Press, 1993)

Fischer, Irmtraud – “The Authority of Miriam: A Feminist Rereading of Numbers 12 Prompted by Jewish Interpretation” in A Feminist Companion to Exodus to Deuteronomy, 2nd series, Athalya Brenner, ed. (Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press, 2001)

Freedman, David Noel – “Moses and Miriam: The Song of the Sea (Exodus 15:1-18,21)” in Realia Dei: Essays in Archaeology and Biblical Interpretation in Honor of Edward F. Campbell Jr. at His Retirement. Scholars Press Homage Series. Prescott H. Williams, Jr., ed. (Duke University Press, 1999)

Graetz, Naomi – “Miriam: Guilty or Not Guilty” Judaism 40.2 (1991) 184-192.

Graetz, Naomi – “Did Miriam Talk Too Much?” in A Feminist Companion to Exodus to Deuteronomy, (Series 1), Athalya Brenner, ed. Feminist Companion to the Bible 6. (Sheffield, Eng.: Sheffield Academic Press, 1994)

Hulse, E.V. – “The Nature of Biblical ‘Leprosy’ and the Use of Alternative Medical Terms in Modern Translations of the Bible” Palestine Exploration Quarterly, 107 (1975) 87-103.

Janzen, J. Gerald – “Song of Moses, Song of Miriam: Who is Seconding Whom?” in A Feminist Companion to Exodus to Deuteronomy, (Series 1), Athalya Brenner, ed. Feminist Companion to the Bible 6. (Sheffield, Eng.: Sheffield Academic Press, 1994)

Labowitz, Shoni – God, Sex and Women of the Bible, Discovering Our Sensual, Spiritual Selves (Simon & Schuster, 2001)

Meyers, Carol L. – “Miriam the Musician” in A Feminist Companion to Exodus to Deuteronomy, (Series 1), Athalya Brenner, ed. Feminist Companion to the Bible 6. (Sheffield, Eng.: Sheffield Academic Press, 1994) 207-30.

Meyers, Carol L. – “The Drum Dance Song Ensemble: Women’s Performance in Biblical Israel” in Rediscovering the Muse, K. Marshall, ed. (Northeastern, 1993)

Meyers, Carol L. – “Miriam, Music, and Miracles,” in Mariam, The Magdalene, and the Mother, Deirdre Good, ed. (Indiana University Press, 2005)

Meyers, Carol L. – “Mother to Muse: An Archaeomusicological Study of Women’s Performance in Ancient Israel” in Altheya Brenner, ed., Recycling Biblical Figures. NOSTER Conference 1997 (Leiden: DEO)

Meyers, Carol L. – “Of Drums and Damsels: Women’s Performance in Ancient Israel” Biblical Archeologist 54 (1991) 16-27

Meyers, Carol L. – Exodus. New Cambridge Bible Commentary. (Cambridge University Press, 2005)

Murphy, Cullen – The Word According to Eve: Women and the Bible in Ancient Times and Our Own (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1998)

Oesterley, W.O.E. – The Sacred Dance (Dover Publications, 2002)

Paz, Sarit – Drums, Women and Goddesses: Drumming and Gender in Iron Age II Israel. Orbis Biblicus et Orientalis. (Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 2007)

Poethig, Eunice – The Victory Song Tradition of the Women of Israel, Ph.D. dissertation from Union Theological Seminary, 1985

Redmond, Layne – When the Drummers were Women: A Spiritual History of Rhythm (Three Rivers Press, 1997)

Schwartz, Rebecca – “Introduction” in All the Women Followed Her: A Collection of Writings on Miriam the Prophet & the Women of Exodus, Rebecca Schwartz, ed. (Mountain View, CA: Rikudei Miriam Press, 2001)

Schwartz, Rebecca – “‘If There Be a Prophet…'” in All the Women Followed Her: A Collection of Writings on Miriam the Prophet & the Women of Exodus, Rebecca Schwartz, ed. (Mountain View, CA: Rikudei Miriam Press, 2001)

Setel, T. Drorah – “Exodus,” in The Women’s Bible Commentary, Carol A. Newsom and Sharon H. Ringe, eds. (Louisville: Westminster John Knox, 1992)

Sheehan, J.F.X. – “The Pre-P Narrative: A Children’s Recital?” in Scripture in History and Theology: Essays in Honor of J. Coert Rylaarsdam. Pittsburgh Theological Monograph Series 17. A.L. Merrill and T.W. Overholt, eds. (Wipf & Stock, 1977)

Simpson, C.A. – The Early Traditions of Israel: A Critical Analysis of the Pre-Deuteronomic Narrative of the Hexateuch (Oxford: B. Blackwell, 1948)

Trible, Phyllis – “Subversive Justice: Tracing the Miriamic Traditions” in Justice and the Holy, Walter J. Harrelson, Douglas A. Knight, and Peter J. Paris, eds. (Atlanta: Scholars Press, 1989) 99-109.

Trible, Phyllis – “Bringing Miriam Out of the Shadows” in A Feminist Companion to Exodus to Deuteronomy, (Series 1), Athalya Brenner, ed. Feminist Companion to the Bible 6. (Sheffield, Eng.: Sheffield Academic Press, 1994)

van der Leeuw, G. – Religion in Essence and Manifestation (Princeton Univ. Press, 1986)

van Dijk-Hemmes, Fokkelien – “Some Recent Views on the Presentation of the Song of Miriam,” in A Feminist Companion to Exodus to Deuteronomy, (Series 1), Athalya Brenner, ed. Feminist Companion to the Bible 6. (Sheffield, Eng.: Sheffield Academic Press, 1994) 200-206.

von Rad, G. – Old Testament Theology: Volume I: The Theology of Israel’s Historical Traditions (Harper & Row, 1967)

I’ve been exploring for a little for any high-quality articles

or weblog posts on this kind of area . Exploring in Yahoo I at last stumbled upon this site.

Studying this info So i am happy to exhibit that I’ve

a very good uncanny feeling I found out just

what I needed. I so much certainly will make certain to don?t disregard this website and

give it a glance regularly.

I’ve also searched for sites that discuss the nitty gritty details of the biblical women. Most of what is available is devotional in nature, which has its place, but we want to know the background material as well. If you want to keep up-to-date on my explorations of all things women of the Bible, make sure to sign up for my newsletter. In the meantime, if you know of any other websites/blogs that offer scholarly analyses of our favorite biblical characters, let me know.