At first glance the servant is a minor, unnamed character. On second glance she is both anonymous and the star of the story. How is it possible to reconcile these two attributes? As Maurice Samuel notes regarding the many unnamed people of the Bible, “Many of them are given only a few lines, and yet their presence can be as solid as that of the principals. They are like great actors with short roles; they are there for a few moments, but they are mightily there.” Are we anonymous stars in our own lives? Are we mightily present in our own destinies? I invite you to ask your own questions of the story and come away with new insights about not just the Bible, but of your place in the world.

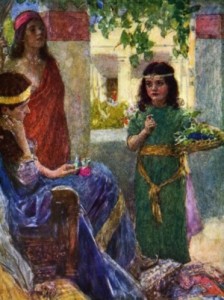

In 2 Kings 5:1-5 we learn of a young Israelite woman captured in war who then becomes the servant of the Syrian commander-in-chief Naaman and his wife. Naaman suffers from leprosy. The young woman suggests to her mistress that Naaman seek out the Israelite prophet Elisha, who she claims can cure his leprosy.

He follows her counsel, first seeking permission from his superior, the King of Aram who then writes the King of Israel requesting that Naaman be healed. The King of Israel tears his clothes and asks rhetorically, “Am I God?” He thinks he has to cure the foreign commander or another devastating war between the two nations will ensue. He completely forgets about the prophet Elisha who has been busy performing some spectacular miracles (for instance, resurrection in 2 Kings 4). The narrator is mocking the powerlessness of the whole chain of authority from mistress, to commander, to foreign king, to the King of Israel. Eventually Elisha cures Naaman by instructing him to bath in the Jordan River, thereby avoiding a war between Syria and Israel. We are witnessing the “Butterfly Effect” wherein the suggestion of one young woman affects international politics.

We as readers are curious. Everyone readily listens to the enslaved Israelite girl’s advice. Why? We are reminded of the story of Joseph where we are told: “Yahweh was with Joseph and he was a successful man… When his master saw that Yahweh was with him and that Yahweh made everything he did successful in his hand, Joseph found favor in his eyes…” (Gen. 39:2-4). Perhaps, like Joseph, there is more going on with this lowly female servant than we thought.

Yes, she seems spirited and forthright and certainly she has not suppressed her personal identity. As Walter Brueggemann writes, “Her forced relocation into Aram has not eradicated or diminished her sense of her true place of belonging. Her capacity to remember may be taken as a mode of acceptable resistance…” (p.53). Brueggemann argues that her resistance is not just political but theological as well. By suggesting that Israel’s God can cure leprosy, she intimates that the Syrian gods are powerless against the disease– a very bold statement to make in a potentially hostile environment.

Furthermore, no prophet has ever cured leprosy before so her pronouncement is astonishing for its confidence in the prophet Elisha. Perhaps she even anticipates that through the healing of Naaman, the Israelite prophet might heal the strife between Syria and Israel. Is Naaman so desperate that he listens to his war captive? I don’t get that impression. When Elisha first instructs Naaman to bathe in the river, the commander is enraged. He expected the prophet to come out to him personally rather than send a servant. He expected Elisha to personally wave his hand over him instead of telling him to go jump in a river. Naaman is pretty impressed with himself, even obsessed with his greatness. He doesn’t seem to be acting out of utter despair. It seems that he went out of his way to yield to his young servant woman’s suggestion. He won’t listen to a great prophet but he does pay heed to his captive slave? Things just don’t seem to add up.

Then I discovered an article by John MacDonald wherein he explores the meaning of na’arah, the Hebrew word used for the servant woman. Usually the term is translated as “young girl in domestic service.” The male form of the word, na’ar is used to describe Esau (Gen. 25:27), Joseph (Gen. 37:2), Shechem the Hivite prince (Gen. 34:19), Joseph’s sons Manasseh and Ephriam (Gen. 48:16), Samson (Judg. 13:5-7,12,24), Samuel (1 Sam 1:22, 24-25)– priests are na’ar (Ex. 24:5; 1 Sam. 2:13, 15), Joshua is Moses’ na’ar (Ex.33:11), even Solomon calls himself na’ar (1 Kings 3:7). As far as the women go, Rebecca is a na’arah (Gen. 24:16) as well as Dinah (Gen. 34:3), Pharaoh’s daughter (Ex. 2:5), Ruth (Ruth 2:5,6), Queen Esther (Esther 2:4) and so on. You get the idea: Naaman’s na’arah is in good company. We are not talking about menial servants here, but young people of high birth.

“The ne’arim are never mere slaves or menial servants. It is probably that in Israelite society, as in the society of Ugarit centuries before, there were distinctive classes or guilds of ne’arim.” (MacDonald, p.150)

Similar to the ne’arim of the Persian king in the Book of Esther (2:2), I believe Naaman’s servant woman was of sufficient rank to make a suggestion that would be heeded by the commander. Based on his research, MacDonald concludes that a na’ar could hold property, wealth, receive gifts from important people and perform the role of an elite military officer (in the case of a man). “Although primarily intended to glorify Elisha, this story also belongs to the genre of traditions that portray women (such as Esther and Judith) exerting considerable influence over foreign leaders despite their lack of authority.” (Burnette-Bletsch, p.275) Suddenly it makes sense that Naaman believes and acts immediately upon his servant’s advice: she is of noble stock and highly esteemed within Naaman’s household.

And her impact on the story continues. The same word to describe the “little captive girl” (as most commentators label her) is also used to describe Elisha’s servant Gehazi. The narrator is using the repetition of the language of master-slave relationship to call our attention to the contrast between Naaman’s servant and Elisha’s servant. So what is Gehazi’s story? After Elisha declines Naaman’s gifts of gratitude, Gehazi runs after the newly healed Syrian commander and greedily asks for the treasures for himself. As a consequence he becomes leprous.

“…Consider the way in which the narrator makes her luminous… how she is to be contrasted with Gehazi… who understands nothing of the transformative faith to which the narrative attests. He is remarkably unlike the young girl… Whereas Gehazi seeks to turn the wonder of the prophet to profit, the young girl seeks nothing, but only gives an account of what she knows and who she is.” (Brueggemann, p.56)

The plot, themes and language of the story have been carefully constructed for maximum irony. And at the very heart of the story lies a distinctive woman who is essential and whose impact is immense.

For Further Reading

Brueggemann, Walter – “A Brief Moment for a One-Person Remnant (2 Kings 5:2-3)” Biblical Theology Bulletin: A Journal of Bible and Theology, vol. 31, #2

Burnette-Bletsch, Rhonda – “Wife and Servant Girl of Naaman” in Carol Meyers, Toni Craven and Ross S. Kraemer, eds., Women in Scripture: A Dictionary of Named and Unnamed Women in the Hebrew Bible, The Apocryphal/Deuterocanonical Books, and the New Testament (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 2000)

Kim, Jean Kyoung- “Reading and Retelling Naaman’s Story (2 Kings 5)” Journal for the Study of the Old Testament, Sept vol 30 (2005) 49-61.

MacDonald, John – “The Status and Role of the Na’ar in Israelite Society,” Journal of Near Eastern Studies, 35,3 (July 1976) 147-170.

Reinhartz, Adele – “The Israelite Servant Girl (2 Kgs 5:1-5)” in ‘Why Ask My Name?’ Anonymity and Identity in Biblical Narrative (New York: Oxford Univ. Press, 1998)

Zamore, Rabbi Mary Lande, “Haftarat Tazri’a” in The Women’s Haftarah Commentary: New Insights from Women Rabbis on the 54 Weekly Haftarah Portions, the 5 Megillot and Special Shabbatot, Elyse Goldstein, ed. (Jewish Lights Publishing, 2008)