At first glance, Hannah’s tale is a typical patriarchal tale reinforcing a woman’s role and function as merely biological; maternal yearnings are not personal but a result of a social setting that prizes women for their reproductive potential above all else.

As one feminist scholar writes, “What seems to be a sentimental narrative about the happy transition from emptiness to fullness and from failure to victory is a carefully constructed story intended among other things to promote the institution of motherhood…The fact is that the annunciation type-scene…drives home the…message: that woman has no control at all over her reproductive potential” (Fuchs, p.129).

Yet taking control of her reproductive potential is precisely what Hannah does. Furthermore, “if Hannah functions only as Samuel’s mother, why did the storyteller digress from the course of his tale to build up a personality of dignity and memorable talents, a woman who is the sole architect of her son’s glorious career?” (Aschkenasy, Woman, p.142). As we will see, Hannah becomes the main character of the plot, immortalized for her character traits, not just her function as the mother of the prophet Samuel. Hannah moves from speechlessness to orator of one of the most eloquent songs of the Bible. By studying the four scenes in which Hannah plays a part, we can watch the process by which Hannah gains her voice and her personal power.

Scene 1

We are introduced to Hannah, the favorite of Elkanah’s two wives. God has closed Hannah’s womb while at the same time Peninnah, the other wife was quite fecund and tormented Hannah for her barrenness. The concept of God closing a woman’s womb is jolting to our modern ears but it was the understanding in the Ancient Near East that certain events were attributable to the divine. That did not mean human actors could not change the course of events. The God of the Hebrew Bible seems quite open to negotiation, to allowing humans to play an active part in the divine plan. Though Hannah’s infertility was divinely mandated “Hannah indeed sets out to change God’s decree” (Aschkenasy, Woman, p.139) like Abraham negotiating for the souls of Sodom.

Due to her infertility Hannah was greatly distressed and was unable to eat when the family traveled to Shiloh to make sacrifices. Barren women were in a precarious economic position since the husband could legally divorce her for not producing an heir (Amit, p.75). Elkanah tried to comfort her by telling her that she would always be provided for. In addition, he asked her, “Am I not more devoted to you than ten sons?” (v.8) Now there is a great deal of debate about whether Elkanah was a complete dolt or a nice guy. Those who find him obnoxious see Elkanah as caring more for his own image by rephrasing her suffering into something about himself. Fewell, Klein and Fuchs offer scathing assessments of his character.

However, I find Aschkenasy’s assessment more convincing:

“Elkanah could have said: ‘Do not worry, Hannah, you are as good to me as ten sons.’ In other words, starting with the premise of the woman’s role as the provider of sons to the male, he could have juxtaposed the ten sons, the contribution that Hannah has failed to make… Instead, Elkanah’s attitude is surprisingly modern; he views himself not as a patriarch who has magnanimously forgiven his wife for not having done her duty to his family, but as the loving partner whose duty it is to make his wife happy… He does not define his relationship with his wife in terms of her familial or sexual duties, in terms of what she has or has not given him, but in terms of his contribution to her contentment: ‘am I not better to thee than ten sons'” (Woman, pp.136-7).

Indeed, Aschkenasy sees Elkanah as a proto-feminist for his enlightened manner. This view seems to be confirmed later when he says, “Do what you like, only– may YHWH establish his word” (v.23). The Greek Septuagint translates the phrase as ‘May YHWH establish what comes from your [that is, Hannah’s] mouth.” In other words, Elkanah not only acknowledged that Hannah was in firm control of events but encouraged her as well. However you view Elkanah, he paradoxically played only a biological role as the impregnator of Hannah and then he receded into the background.

Though Hannah was silent in the first scene, she does not respond to the taunts of her co-wife, never showed envy of Peninnah and remained dignified throughout her ordeal. Her name encapsulates these elements of her character. “Hannah’s name, which comes from the root h-n-n, and has two possible meanings. The primary meaning of this root is ‘to be gracious’ or ‘to show favor’… The secondary meaning of the same root is ‘to be loathsome.’ This meaning may have been hinted at in the initial treatment Hannah received from her-co-wife, Peninnah… The two meanings inherent within Hannah’s name speak to her experience…” (Bronner, p.33).

Scene 2

In the second scene Hannah entered the shrine at Shiloh to pray silently to God in front of the ark. At that time, religion was a family matter wherein men and women performed many of the same ritual activities, except for the priesthood (Cook, p.39).

“While her household is busy offering sacrifices at Shiloh, Hannah steps quietly into the courtyard reserved for priests…Eli sees her and mistakenly exercises his authority as priest of the gate by labeling her a drunkard and expelling [sic] her… Ironically… a child who would abstain from wine and beer throughout his life so that he could serve Yahweh worthily in the courtyard where Hannah is praying…” (Matthews/Benjamin, p.195).

It is startling to find that she seems to be very close to the Holy of Holies inside the tent of meeting when she prays to God and makes her vow to dedicate her future son to the shrine.

In addition, “Hannah prays close to where Eli the chief priest is standing, and he takes notice of her. Perhaps she intends him to…” (Jobling, p.132). Eli mistook the soundless movement of her lips as a sign of drunkenness and confronted her. For the first time Hannah spoke out loud and the “very first word she speaks out loud in the story is to the chief priest of Israel, and it is ‘No’!” (Jobling, p.132). Eli mistook her prayer for drunkenness because private prayer in the sanctuary had never been practiced before. The high priest was used to public worship and sacrifice, not to an individual speaking from the heart. Her confidence that she could approach God directly without an intermediary was novel. “Until the moment Hannah speaks in her heart,’ all liturgical speech in the Tabernacle has been public, representative, communal, a gathering-platform… Hannah is a heroine of religious civilization because she invents, out of her own urgent imagining, inward prayer” (Ozick, p.89). It is in this silent prayer that Hannah asked God for a son and vowed to dedicate him to the service of Yahweh.

But why? Obviously she was not motivated by the desire to bear a son to Elkanah because she vowed to give the child away. “Nothing in the text suggests that Hannah wants a child because Peninnah has children or because Peninnah taunts her. Hannah’s desire arises from within and is maintained as a personal, as yet unfulfilled wish” (Klein, p.45). Hannah seemed to have a specific plan for she “maps out her son’s future as a man of God even before she is assured that her prayer will be answered” (Aschkenasy, Eve’s Journey, p.12). She determined that he will be a nazarite, “I will give him to the Lord all the days of his life, and no razor shall come upon his head” (1 Sam. 1:11). “Her vow opens up another possibility, that what she wants is a son in the service of YHWH, a son being prepared for a position of leadership in Israel” (Jobling, p.132). It seems that her desire for a child and her vow were her way of making her mark in the world, of making a lasting impact.

Though many feminists argue that the desire to have children is merely a conditioned response to patriarchy’s need for male heirs, I take issue with this model of motherhood. It is certainly true that the barren mothers of the Bible desire sons, rather than daughters so the feminist critique has some validity. We can condemn her for not wanting a child regardless of gender. However, she seemed to want a son not for the economic security he could provide in her old age or for the benefit of her husband. These outcomes were not possible since she vowed to dedicate the son to God. Rather I see Hannah’s maternal yearnings as an expression of her ambition and of her creativity. Realistically only a son could fulfill her designs. Even if her son did not rise to prominence later, thereby making the story of national importance, her desires were in her interest, not in the interest of her husband. We also learn from Hannah’s story that mothers had the power to dedicate their sons to cultic service, that her vow had legal force and was socially approved (Bronner, p.32). According to Numbers 30, it would have been possible for Elkanah to cancel Hannah’s vow but there is no evidence that she even consulted him.

Her vow showed complexity and depth, not unlike her character.

“Hannah’s negotiating tactics are cleverly made up of several clearly defined steps. First, her address to God is couched in the language of an oath, thus endowing it with the sanctity of a promise made to God. Instead of asking, Hannah frames her request within a sacred vow. She displays humble deference to God that is nevertheless combined with great tenacity. Although prefacing her entreaty to God with the conditional, tentative ‘if,’ and modestly referring to herself as God’s ‘handmaid,’ Hannah seems to be resolved not to leave God empty-handed” (Aschkenasy, Woman, p.138).

In essence, Hannah has made a contract with God. Jarrell even suggests that birth narratives such as those of the matriarchs, were equivalent to the covenants that God made with the patriarchs.

Finally, before moving on to the next scene I would like to address an intriguing analysis I discovered in the course of my research. I highly recommend “Hannah’s Desire” and “Contexts for Hannah,” two chapters in Jobling’s marvelous book, 1 Samuel. He notices that the high priest Eli’s two sons, Hophni and Phinehas are mentioned in passing early in Hannah’s story (1:3). Later we learn that the sons are wicked priests who take more than their share of sacrifices, curse God and have sex (perhaps rape?) the women who serve at the entrance to the tent of meeting. “The text insists that they mistreat every worshiper in the same way: ‘When anyone offered sacrifice’ (2:13), ‘This is what they did…to all the Israelites’ (v. 14). If to all, then to Elkanah and Peninnah and Hannah… year by year, as she attended the feast, Hannah experienced the rottenness of the priestly regime” (Jobling, p.134). Knowing these things about the priests, the embodiment of political power in Israel, why does she want to bring her son into contact with them? Jobling posits that by dedicating her son to the shrine, she is making a public statement, an attempt to intervene in the appalling situation. She has elevated her personal situation into a national cause by raising a son to correct the ills of society.

Scene 3

Hannah finally gave birth to a son and named him Samuel, meaning something like, “his name is God.” In the same way that the patriarchs’ named wells, springs and other places thus establishmenting their rights of control, “the child receiving the name thereby comes under the influence of the namegiver” (Meyers, Hannah Narrative, p.121). It was believed in the Ancient Near East that a child’s name shaped his or her character and in many cases his or her livelihood as well. By naming Samuel, Hannah took on a role of authority and responsibility for what kind of person her son would be (Cook, p.52).

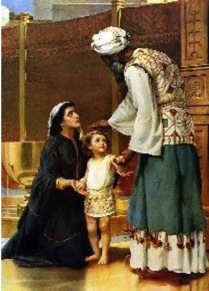

After weaning Samuel, she took him to Shiloh and delivered him into the hands of Eli the priest as she promised. Interestingly, she didn’t quite relinquish the child but merely lent him to God: “For this child I prayed; and the Lord has granted me my request that I have asked of Him. Therefore also I have lent him to the Lord, for all his life he will be borrowed by the Lord” (1:27). In other words, she maintained her control over her son even though he was being raised in the sanctuary. She also spoke boldly to the high priest as one who knows that God listens to her.

Scene 4

At the time that Hannah had appointed, the family returned to Shiloh to make sacrifices and deliver Samuel. The text is very clear that she was the one who brought him to the House of the Lord and she was the one who spoke to the high priest Eli. She bowed down before God and prayed/sang her famous song. Most commentators conclude that the song is of a later date than the composition of the narrative and was inserted by a later compiler. Despite this being an addition, the intention was to attribute the song to her, to put the words in her mouth and name her as the author.

The result is that “by presenting her as one of Israel’s poets and singers [the narrator] puts her in the company of Miriam and Deborah, women who also sang triumph-songs and were leaders in Israel… as if her dedication of Samuel were an act of leadership on a par with the defeat of the Canaanites or even with the crossing of the Sea!” (Jobling, p.136).

In the final form of the story we are encouraged to assume that Hannah was an unusually gifted woman and probably was regarded as a leader in Israel (Vos, p.154). Jobling finds it of particular note that she sang her extraordinary song not when she discovered she was pregnant or when her son was born but when she dedicated Samuel to God. He concludes that her purpose for wanting a child all along was to make an impact on history, to shape the course of events by bringing her righteous son to the highest seat of power at that time. “Hannah interprets the successful outcome of her struggle to become a mother as a victory that is social and moral rather than feminine and biological” (Aschkenasy, Woman, p.142). Her song of how God lifts up the lowly and the powerless shifts the focus of the story from a traditional domestic narrative to a social critique of her time, a remarkable point to make in the presence of the priests who are abusing their power. What seemed like the typical story of a barren mother wanting a son concludes as a story of a great woman who is not only aware of her people’s needs but takes the initiative to change the course of events for the better.

For Further Reading

Adelman, Penina – Praise Her Works: Conversations with Biblical Women (The Jewish Publication Society, 2005)

Amit, Yairah – “`Am I Not More Devoted to You Than Ten Sons?’ (1 Samuel 1.8): Male and Female Interpretations,” in Feminist Companion to Samuel and Kings, Athalya Brenner, ed., A Feminist Companion to the Bible 5. (Sheffield, Eng.: Sheffield Academic Press, 1994) 68-76.

Aschkenasy, Nehama – Women at the Window: Biblical Tales of Oppression and Escape (Michigan: Wayne State University Press, 1998)

Bronner, Leila Leah – Stories of Biblical Mothers: Maternal Power in the Hebrew Bible (Dallas: University Press of America, 2004)

Brueggemann, Walter A. – “I Samuel 1:1: A Sense of a Beginning,” Zeitschrift fur die Alttestamentliche Wissenschaft 102 (1990) 33-48.

Cook, Joan E. – Hannah’s Desire, God’s Design: Early Interpretations of the Story of Hannah. Library Hebrew Bible/Old Testament Studies 282. (Bloomsbury T&T Clark, 1999)

Falk, Marcia – “Reflections on Hannah’s Prayer,” Tikkun 9, no . 4 (1994) 61.

Fewell, Danna Nolan and David M. Gunn – Gender, Power, and Promise: The Subject of the Bible’s First Story (Nashville: Abingdon Press, 1993)

Fuchs, Esther – “The Literary Characterization of Mothers and Sexual Politics in the Hebrew Bible” in Feminist Perspectives on Biblical Scholarship, Adele Yarbro Collins, ed. (Atlanta: Scholars Press, 1985) 117-36.

Jarrell, R.H – “The Birth Narrative as Female Counterpart to Covenant,” Journal for the Study of the Old Testament 97 (2002), 3-18.

Jobling, David – 1 Samuel (Collegeville, MN: Liturgical Press, 1998)

Klein, Lillian R. – “Hannah: Marginalized Victim and Social Redeemer,” in From Deborah to Esther: Sexual Politics in the Hebrew Bible (Minneapolis: Fortress, 2003)

Matthews, Victor H. and Don C. Benjamin – Social World of Ancient Israel 1250-587 BCE (Hendrickson, 1993)

Meyers, Carol – “The Hannah Narrative in Feminist Perspective” in Go to the Land I will Show You: Studies in Honor of Dwight W. Young, Joseph E. Coleson and Victor H. Mathews, eds. (Winona Lake, Ind.: Eisenbraun, 1996)

McKenna, Megan – Leave Her Alone (Orbis Books, 1999)

Nowell, Irene – Women in the Old Testament (Collegeville, Minn.: Liturgical, 1997)

Ozick, Cynthia – “Hannah and Elkanah: Torah as the Matrix for Feminism” in Out of the Garden: Women Writers on the Bible, Christina Buchmann and Celina Spiegel, eds.(Ballantine Books, 1995)

Vos, Clarence J. – Woman in Old Testament Worship (Amsterdam: Judels & Brinkman, 1968)