Deut. 17:15 -17 admonishes the people of Israel to not let their king, probably Solomon, have lots of wives. Since the patriarchs and King David were polygamists, this critique of King Solomon seems unwarranted at first reading. As I explored all the references to Solomon’s wives and concubines I found varied and contradictory assessments of the king, from expressions of national pride to severe condemnation, particularly for his marriage to Pharaoh’s daughter. Since Pharaoh’s daughter is the first mentioned in the list of Solomon’s wives in 1 Kings 11:1, she came to symbolize Solomon’s harem as a whole (Reinhartz, Why, p.25).

Cohen has an interesting thesis for why Solomon’s Egyptian wife gave rise to such a wide range of opinions about both the king and the rest of his women. He argues that with each successive redaction of these accounts, commentators began adding critiques of Solomon in light of the historical events of their own time. Let’s start with the initial stage. Cohen sets out the six scriptural references to Solomon and his marriage to the daughter of Pharaoh and notes that five of the passages (1 Kgs. 3:1, 1 Kgs. 7:8, 1 Kgs. 9:16, 1 Kgs. 9:24, and 2 Chron. 8:11) show no condemnation of the marriage. “On the contrary, the literary context of these verses implies that the marriage and the events associated with it (the conquest of Gezer and the building of a separate palace for the princess) belong to the glorious achievements of Solomon’s reign” (Cohen, p. 24). Furthermore, the “author of Chronicles does not condemn either the marriage or any other act of Solomon. In his account, Solomon’s treatment of his Egyptian wife is a lesson in piety from a model king and husband” (Cohen, p.37). The king’s harem of 700 wives and 300 concubines was even seen by the narrator as further evidence of the splendor of his reign. The marriages signified Israel’s entrance onto the international stage of trade and alliances and therefore were a source of patriotism. In Solomon’s time, the inclusion of his wife’s deities in the cult of Yahweh was an unremarkable policy. The “Yahweh-only” concept did not develop until later (Burns, p.33).

Then as the kingdom of Israel disintegrated after Solomon’s death, the biblical historians blamed his wives and concubines for turning the king away from God (1 Kings 11:1-2). Sweeney argues that Solomon’s wives were used as a foil against Josiah, the ideal king of the later Deuteronomist writers. “Solomon causes the fundamental problems within the kingdoms of Israel and Judah that Josiah attempts to set aright” (Sweeney, p.609). The king’s marriages were denounced because either the women caused him to worship other gods (1 Kgs. 11:7-8) or at least he allowed his foreign wives to do so (1 Kgs. 11:1). At this early stage of knocking Solomon down a few notches, he was not censured for marrying foreign women. The Deuteronomic historian recorded a number of Israelites marrying foreigners without rebuke.

In the next stage of the reevaluation of Solomon, the foreignness of his wives were denounced. For instance, in a speech against intermarriage Nehemiah preaches, “Did not Solomon king of Israel sin on account of such women?” (Neh.13:26). At the time of Nehemiah, Israel was struggling with national identity after returning from the Babylonian/Persian exile. Ezra and Nehemiah feared that foreign women would not accept the laws and customs of their husbands and thereby their presence would lead to the extinction of the culture and its values. Along with Ezra, Nehemiah determined that God required all the men to cast off their foreign women and children for the purity of Israel. Thus the vilification of Solomon’s foreign women was a reflection of the later historical stresses facing Israel.By the time of the writing of Deut. 17:14-20 the attitudes had changed and foreign wives and Egyptian horses were no longer a source of national pride.

In the final stage, Josephus and rabbinic literature report that is was the primary wife, Pharaoh’s daughter, who led Solomon astray and therefore caused the eventual destruction of Israel.

“Because neither her words nor her actions are conveyed, the reader has no basis on which to evaluate her culpability [in the fall of Solomon’s kingdom]. To the sympathetic reader, the woman appears caught between two sets of norms that entail different assessments of the alliance that her dual role as Pharaoh’s daughter and Solomon’s wife symbolizes. According to the norms of statesmanship, which Solomon followed in marrying her (3:1), the woman binds the states of Egypt and Israel as allies” (Reinhartz, Why, p.25).

The bits and pieces we have about Solomon’s wives do not provide us with any personal information about the women; rather their presence alerts us to the political atmosphere of that era and the subsequent reconstructions of their historical importance.

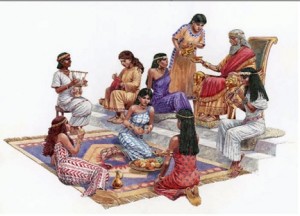

The Palace of Pharaoh’s Daughter

We know a few more details about Solomon’s Egyptian wife. For instance, after Solomon built the city of Gaza, the king of Egypt razed it. Then obviously the two monarch’s made peace and Solomon married the Pharaoh’s daughter. Her father then gave her the smoldering remains of Gaza. “Thanks, dad,” is all I can say. Should I dare ask who ended up with her dowry?

In 2 Chron. 8:11 we find Solomon’s words: “My wife shall not live in the house of David king of Israel, for the places to which the ark of the Lord has come are holy” (2 Chron. 8:11). Therefore Solomon built a palace for Pharaoh’s Daughter outside the city of David. In the Book of Kings, Pharaoh’s daughter moved outside the city of her own accord but in Chronicles she was moved by Solomon. “Thus Chronicles explains what Kings leaves unsaid: that Solomon’s high born Egyptian wife was a threat to the Holy City’s purity” (Schearing, pp.443-4). The commentators argue over whether she was considered impure by reason of being a woman who menstruated or because intercourse was prohibited within the city of the sanctuary. It appears that menstruating women were allowed in the first temple precincts: “…the exclusion of zabim (a category which probably includes menstruants) and those who suffer corpse–impurity is mentioned nowhere else aside from the utopian demand of Num. 5:1-4. Nowhere else in the Hebrew Bible is there a reference to the pollution, or possible pollution, of the sancta by a menstruant” (Cohen, p. 35). In fact, every seven years everyone, including women, were to gather at the sanctuary for the reading of the Law (Deut. 31:11-13). 2 Chron. 20:13, Ezra 10:1, 1 Sam. 1:9-18, and 2 Kings 11:13-16 all mention women who gathered at the temple to pray. And of course there are the women who ministered outside the sanctuary. “None of these passages evince any concern that the women involved might be impure and might pollute the sacred through their impurity” (Cohen, p.35).

In time it was determined that if Pharaoh’s daughter’s palace lay within the Temple precincts there would be the possibility that Solomon might have intercourse too close to the Holy of Holies. This appears to anticipate the religious interests of a later time. “Solomon’s concern in Chronicles that his Egyptian wife not reside in an area sanctified by the ark is a forerunner of the kind of piety which later developed in rabbinic Judaism” (Cohen, p.37). It was this fear of sexual pollution that was emphasized by the post-biblical documents the Damascus Covenant and the Temple Scroll which explicitly prohibited intercourse with a woman within a certain proximity to the ark.

In contrast to his Egyptian wife’s home, Solomon’s palace was within the Temple precincts and I would assume that he kept some of his other women in his home. I can think of several creative ways to prevent Solomon from being a sexist hypocrite: maybe he only had intercourse with Pharaoh’s daughter and kept the other women just for political alliances. Or… It’s hard not coming to the conclusion that something is amiss here. I remember walking through the archaeological park of the city of David with my father several years ago. Though only a small portion of the city has been excavated, we were astounded by how many structures could be identified by educated guesses. The sites of both David and Solomon’s palaces have also been approximated and await “the matter of property rights,” as our very generous Arab guide explained. I can only hope that someday they will uncover the Egyptian wife’s palace as well and find some answers to how much the king really did love Pharaoh’s daughter.

For Further Reading

Burns, John Barclay – “Solomon’s Egyptian Horses and Exotic Wives [intertextual approach to 1 Kgs 10:23-11:43 and 2 Chr 1:14-17,9:22-31],” Forum 7 (1991), 29-44.

Cohen, Shaye J.D. – “Solomon and the Daughter of Pharaoh: Intermarriage, Conversion, and the Impurity of Women” Journal of the Ancient Near Eastern Society of Columbia University 16-17 (1984-5) 23-37.

Malamat, A. – “Is there a Word for the Royal Harem in the Bible? The Inside Story’, in D.P. Wright, et al (eds.), Pomegranates and Golden Bells: Studies in Biblical, Jewish, and Near Eastern Ritual, Law and Literature in Honor of Jacob Milgrom (Winona Lake, IN: Eisenbrauns, 1995) 787-87.

Olley, J.W. – “Pharaoh’s Daughter, Solomon’s Palace, and the Temple: Another Look at the Structure of 1 Kings 1–11,” Journal for the Study of the Old Testament 27 (2003), 355-69.

Reinhartz, Adele – “Why Ask My Name?” Anonymity & Identity in Biblical Narrative (New York: Oxford Univ. Press, 1998)

Reinhartz, Adele – “Anonymous Women and the Collapse of the Monarchy: A Study in Narrative Technique,” in A Feminist Companion to Samuel and Kings, 1st series. Athalya Brenner, ed. Feminist Companion to the Bible 5. (Sheffield, Eng.: Sheffield Academic Press, 1994) 43-65.

Schearing, L.S. – “A Wealth of Women: Looking Behind, Within, and Beyond Solomon’s Story,” in L.K. Handy, ed. The Age of Solomon: Scholarship at the Turn of the Millennium. Studies in the History and Culture of the Ancient Near East, V. 11. (Brill, 1997)

Sweeney, Marvin – “The Critique of Solomon in the Josianic Edition of the Deuteronomistic History,” Journal of Biblical Literature 114 (1995) 607-622.