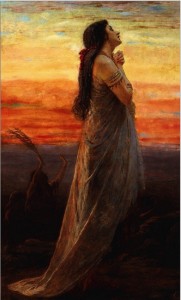

“Then the Spirit of the Lord was upon Jephthah And Jephthah made a vow to the Lord and said, “If you will give the Ammonites into my hand, then whatever comes out from the doors of my house to meet me when I return in peace from the Ammonites shall be the Lord’s, and I will offer it up for a burnt offering.” So Jephthah crossed over to the Ammonites to fight against them, and the Lord gave them into his hand… Then Jephthah came to his home at Mizpah. And behold, his daughter came out to meet him with tambourines and with dances. She was his only child; besides her he had neither son nor daughter. And as soon as he saw her, he tore his clothes and said, ‘Alas, my daughter! You have brought me very low, and you have become the cause of great trouble to me. For I have opened my mouth to the Lord, and I cannot take back my vow.’ And she said to him, ‘My father, you have opened your mouth to the Lord; do to me according to what has gone out of your mouth, now that the Lord has avenged you on your enemies, on the Ammonites.’So she said to her father, ‘Let this thing be done for me: leave me alone two months, that I may go up and down on the mountains and weep for my virginity, I and my companions.’ ” (Judges 11:29-37)

The judge and general Jephthah maked a vow to sacrifice the first thing that came out of his house when he returned victorious from battle. When it was his daughter who danced out of his house, he maked no effort to rescind his oath. To further complicate matters, Jephthah made his vow under the influence of the Spirit of Yahweh. His military victory seems to be a tacit acceptance by God of the terms of his vow. Lev. 27:1-8 stipulates a payment can be made to annul a vow made to God. My first question is obvious. Wasn’t there a way to avert this tragedy?

After the sacrifice, he retains his position as a judge and is remembered as a great military hero (1 Sam. 12:11). Even in the New Testament he is glorified (Heb. 11:32-34). “Nor do the people, exulting in victory, step in to ransom Jephthah’s daughter, as the people ransomed Jonathan from the oath of his father Saul (1 Samuel 14). No solace comes from God either, no ram in the thicket… She accepts her fate so willingly and obediently that it is shocking…” (Exum, Tragedy, p.58). Incongruently, Leviticus 20:2 and Deuteronomy 18:10 specifically outlaw human sacrifice. How are we to make sense of Jephthah’s slaughter? Why was such a horrific story left in the canon?

Literarily we are being set up for the sacrifice. “‘Jephthah’ is an abbreviated form of the Hebrew phrase ‘God opens [the womb],’ which recalls God’s claim on the ‘firstlings’ of the Israelites. “Sanctify upon Me all the first-born,” says God to his Chosen People after liberating them from slavery in Egypt, “Whatsoever openeth the womb among the children of Israel, both of man and of beast, it is Mine” (Exod. 13:2)” (Kirsch, p.213). In reading Jephthah’s name we are to recall that the firstborn belonged to God (Ex. 13:2). “During the formative period of the Federation of Israel, there is the strong implication that human sacrifice was practiced by the people as an acceptable aspect of their Yahwistic belief.” (Green, p.199) As the ancient Israelite religion evolved, the practice was replaced with laws requiring a payment (“redemption”) in place of taking the life of a human being. Many scholars believe that the story of Jephthah predates the laws of redemption.

The use of the phrase “and she was his only child” emphasizes the connection between Jephthah’s daughter and the story of Isaac’s near sacrifice where Abraham is told, “Take now your son, your only son.” Jephthah might have thought he was being tested like Abraham and he expected God to stop his sacrifice as well. “…[O]ther biblical makers of vows used similar formulations and were not punished… Abraham relied on God to provide a fitting sacrifice when he said to Isaac: ‘My son, God will provide himself a lamb for sacrifice’ (Gen. 22:8). Why, then, could Jephthah not rely on God to guide events so that a suitable sacrifice would emerge from his house?” (Valler, p.54) Compared to the Abraham and Isaac story, God is conspicuously missing from the Jephthah incident.

We could assume that she consents to her death for the purpose of national security; she does not wish to jeopardize future military victories by violating her father’s oath. Or perhaps it is out of an extreme sense of integrity that she refuses to violate the vow. “A protest against her position as a sacrificial offering would be a protest against Yahweh who accepted the terms of Jephthah’s vow” (Tapp, p.170). Some commentators insist that the story is left in the canon because she poses no threat to the patriarchal system. Her ready acceptance absolves her father, God and society of responsibility. We are warned that the more we honor her for her willingness, the more we cooperate in victimizing her. “Praising the victim can, however, be as dangerous as blaming the victim.

The problem lies in… a way of structuring experience that ignores the complicity of the victim in the crime… If we allow the women’s ceremonial remembrance to encourage glorification of the victim, we perpetuate the crime. How do we reject the concept of honoring the victim without also sacrificing the woman?” (Exum, Fragmented Women, pp. 35-6)

Some interpreters suggest that the Jephthah account serves to illustrate the steady rejection of God and the withdrawal of the divine in the Book of Judges. “God had been abandoned so many times by Israel and remembered again only when the people are under major threat that, by the time of Jephthah, God has grown impatient with the troubling of Israel (10:6…). Yahweh is merely another party to be bargained with and, once the victory is granted, to be dispensed with, like the daughter.” (Fewell, Judges, p.71-2). The Israelites have rebelled against Yahweh so often that God gives up and refuses to intervene: “therefore I will not continue to deliver you” (Judges 10:11-14). However, it appears that God can’t stop interacting with the Children of Israel. Despite the lawlessness of the people, the Spirit of God rests upon Jephthah. Though we may ignore our scruples and thereby lose the ability to make good choices, the “still small voice” continues to lurk, ready to be listened to.

I suggest that God lurks in the actions of the daughter. Although the ancient Israelites considered Jethphah the hero and his daughter a willing victim, we can read the story for the moral and social flaws she exposes to our view. Note that she hardly acts like someone surprised by how events unfold once she greets her father. She already knew what was going to happen.

“Jephthah’s vow was most likely made in public at Mizpah in order to rouse zeal for the war effort… Hence, Jephthah’s pained exasperation with his daughter: Did she not know better? Had he not make it plain? Has she done this on purpose to wound him, her father?… She has stepped forth aware of her fate. Her voluntary action passes judgment on her father’s willingness to bargain for glory with the life of another. His priorities (and perhaps those of all Israel) stand condemned” (Fewell/Gunn, p.127).

What would be her motivation for purposely walking through the open door to celebrate her father’s return? I propose that she is like a hunger striker willing to die in an attempt to change the social system and thereby prevent future human sacrifice. Her protest begins when Jephthah blames her: “Ah, my daughter, you have brought me very low and have become the source of my trouble.” However, she does not take the blame; rather she places it squarely on her father. “You have opened your mouth to Yhwh; do to me according to what has gone forth from your mouth…” (emphasis mine). She publically proclaims that the responsibility for her death lies with her father.

In addition, she retains the power to name the terms and timing of her death. She announces that she will spend two months in the mountains with her companions.

“[T]he mountain in the Genesis scene becomes a place of communication with God. Just as Moses receives the Ten Commandments on Mount Sinai, Abraham encounters an angel of God and is told that the covenant will proceed. Jephthah’s daughter spends two months in the mountains with her friends… If mountaintops are places of communication with the deity, it is left to our imagination to speculate about what happens among the women.” (Miller, p.38)

After her death the women of Israel continue to recount the daughter’s story for four days every year. “What makes the story of Jephthah’s daughter distinctive is that at the moment of crisis, when a community’s moral system has proven flawed, when the way people relate to God and each other has gone off course, a group of women make a spiritual journey together. They, who have witnessed all that has gone wrong in their society, take time out to create the story that will offer testimony–and perhaps create the building blocks for a new civilization.” (Ochs, p.86)

Like the daughter, we have the opportunity to stand back and make an assessment of our society where child “sacrifice” is alive and well, where daily daughters continue to be abused. There is a strategy for change in her story, a vision of finding life and justice through communal recollection. “In the absence of God’s intervention, human beings and their social system must prevent such horrors” (Frymer-Kensky, p.116). I believe that the narrator intended us to be horrified by the violence of the story and that we should be equally horrified by our own violent world.

“We probably know submissive women like Jephthah’s daughter, arrogant and trapped men like Jephthah, and absent mothers of abused girls. We are prone to criticize women who return to abusers, men who lack imaginative solutions to problems, and a culture of war that destroys families. The ancient stories are really our own stories.” (Miller, p.106)

Are we going to be like the people exulting in Jephthah’s victory, unwilling to step in and stop the injustice we witness? Like the ancient custom of recalling her story each year, through our acts of justice we memorialize the unnamed daughter.

Excursus

It is generally agreed that the Jephthah story has been redacted by the Deuteronomists. Since the same Deuteronomists refer to him as the “savior of Israel” we would expect the saga to be edited so that the hero complies with the laws. Why didn’t the story get cleaned up? Some interpreters solve this conundrum by concluding that his daughter was not actually killed. Here are the clues they marshal for this argument as summarized by David Marcus:

- The phrase in the vow wehãyãh laYHWH can only mean consecration, not offering of a sacrifice.

- The emphasis in the text is on the daughter’s virginity. The text states that the fulfillment of the vow was that “she did not know a man.”

- It is the conclusion of voluntary celibacy, which was unique in Israel, that forms the basis for the annual celebration of the unmarried maidens.

- There is some evidence in the Hebrew Bible, and parallels in other ancient cultures, of women consecrating themselves or being consecrated to sanctuary service, and having to live a life of chastity in this service.

- It is not stated in the text that Jephthah put his daughter to death.

- If the daughter was going to die, she would lament not only her virginity but also her life, and would want to spend her last days with her father, not away from him.

- There is no condemnation of Jephthah anywhere in the Hebrew Bible which implies that his vow and subsequent fulfillment must have been consistent with the laws of Israel; hence, it was not human sacrifice.

- Structural parallels with the Isaac story indicate a non-sacrificial conclusion.

In this analysis, Jephthah’s daughter remained a virgin and spent the rest of her life consecrated to God, wandering the hills of Israel.

For Further Reading

Bal, Mieke – Death and Dissymmetry: The Politics of Coherence in the Book of Judges (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1988)

Bal, Mieke – “Between Altar and Wondering Rock: Toward a Feminist Philology” in Bal Mieke, ed., Anti-Covenant: Counter- Reading Women’s Lives in the Hebrew Bible. Bible and Literature Series 22. Journal for the Study of the Old Testament: Supplement Series 81 (Sheffield, Eng.: Almond, 1989)

Berquist, J.L. – Reclaiming her Story: The Witness of Women in the Old Testament (St. Louis: Chalice, 1992)

Exum, J. Cheryl – Fragmented Women: Feminist (Sub)versions of Biblical Narratives. Journal for the Study of the Old Testament: Supplement Series 163 (Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press, 1993).

Exum, J. Cheryl – Tragedy and Biblical Narrative: Arrows of the Almighty (Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Press, 1992).

Exum, J. Cheryl – Signs and Wonders: Biblical Texts in Literary Focus. Society of Biblical Literature Semeia Studies (Society of Biblical Literature, 1989)

Fewell, Danna Nolan and David M. Gunn – Gender, Power, and Promise: The Subject of the Bible’s First Story (Nashville: Abingdon Press, 1993)

Fewell, Danna Nolan – “Judges,” in C.A. Newsom and S.H. Ringe, eds., The Women’s Bible Commentary (Louisville, KY: Westminster/John Knox Press, 1992)

Frymer-Kensky, Tikva – Reading the Women of the Bible: A New Interpretation of their Stories (New York: Schoken Books, 2002)

Fuchs, Esther – Sexual Politics in Biblical Narrative: Reading the Hebrew Bible as a Woman (Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press, 2000)

Green, Alberto R.W. – The Role of Human Sacrifice in the Ancient Near East. American Schools of Oriental Research Dissertation Series 1. (Missoula, Mont.: Scholars Press, 1995)

Kirsch, Jonathan – The Harlot by the Side of the Road: Forbidden Tales of the Bible (Ballantine Books, 1998)

Marcus, David – Jephthah and His Vow (Texas Tech University Press, 1986)

Miller, Barbara – Tell It on the Mountain: The Daughter of Jephthah in Judges 11. Interfaces series. (Liturgical Press, 2005)

Ochs, Vanessa L., Ph.D. – Sarah Laughed: Modern Lessons from the Wisdom & Stories of Biblical Women (McGraw-Hill, 2005)

Sawyer, Deborah F. – God, Gender and the Bible (London: Routledge, 2002)

Tapp, Anne Michele – “An Ideology of Expendability: Virgin Daughter Sacrifice in Genesis 19:1-11, Judges 11:30-39 and 19:22-26” Bal, Mieke, ed., Anti-Covenant: Counter-Reading Women’s Lives in the Hebrew Bible (Sheffield, Eng.: Almond, 1989) 157-74.

Trible, Phyllis – Texts of Terror: Literary-Feminist Readings of Biblical Narratives. Overtures to Biblical Theology. (Philadelphia: Fortress, 1984)

Valler, Shulamit – “The Story of Jephthah’s Daughter in the Midrash” A Feminist Companion to Judges (Second Series), Athalya Brenner, ed. Feminist Companion to the Bible. (Bloomsbury T&T Clark, 1999)