I sit up straight in my chair when Harvard Divinity School hosts a site under its auspices with the banner, “Gospel of Jesus’s Wife“. For years I’ve read the Harvard Theological Review (HTR), a publication of the aforementioned institution, and I’ve learned first-hand that the HTR publishes articles of the highest quality. The authors invariably provide deep analyses and sometimes startling, but sound conclusions. Startling because often times no one has followed through the previously well-studied data to the logical conclusion.

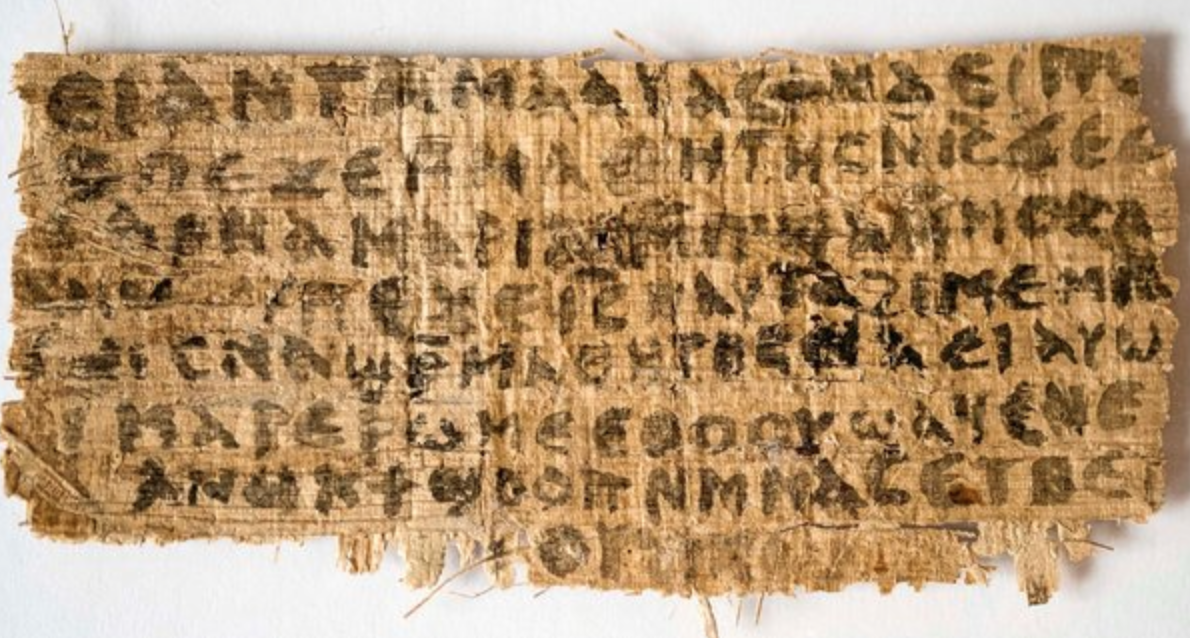

All right, enough fawning over HTR. Let’s get down to business. On April 10, 2014, via a press release, Harvard Divinity School announced that based on a preponderance of evidence, the ancient fragment nick-named the “Gospel of Jesus’s Wife” is not a forgery. In the fall of 2012 at the International Coptic Congress in Rome, Professor Karen L. King announced the existence of a papyrus fragment containing the words, “Jesus said to them, my wife…”

“Twice in the tiny fragment, Jesus speaks of his mother, his wife, and a female disciple—one of whom may be identified as ‘Mary.’ The disciples discuss whether Mary is worthy, and Jesus states that ‘she can be my disciple’” (Beasley).

Nothing is known about where the one-and-a-half inches by three inches papyrus fragment came from except that it is written in Coptic, an early Christian language used in Egypt. Extensive research has determined that the document dates to between the sixth and ninth centuries CE with indications that the text may have originally been composed between the second to the fourth centuries CE. The big news is that extensive analysis of the papyrus, the ink, the handwriting, grammar, radiocarbon testing as well as a bunch of other cutting-edge technology confirms that the document is not a forgery and that it is indeed an ancient text and a product of the early Christian community.

In 2012, Dr. King’s announcement of the existence of the fragment instigated a firestorm of protest from a variety of traditionally-minded sources who immediately described the document as a forgery. For example, Dr. Depuydt, an Egyptologist at Brown University, claimed that testing the fragment was irrelevant. After seeing a newspaper photograph of the text he saw “no need to inspect it” because to him it was obviously a fake. An editorial in the Vatican’s newspaper also declared it a fake before the text had been put to any scientific testing.

“But even some of those casting doubt are also applauding her work. Many scholars said in interviews that they were excited by the discovery, because if it is genuine, it suggests at least one community of early adherents to Christianity believed that Jesus was married” (Goodstein, “Coptic”).

King has never advocated that the fragment provides evidence that Jesus was married. Rather, the document reveals that the early Christian community wondered if Jesus had been married or not. King contends that the community that might have produced this document debated “whether it was better for Christians to be celibate virgins or to marry and have children.” The early Christian community expected the immanent “Second Coming” of Jesus when he would reign over the world, mete out justice and instigate the general resurrection. Whatever previously constituted normal life, such as procreation and sustaining future generations, was meaningless in the face of waiting for the “angelic life of the resurrection” (Seim, p. 257). What was the point of marriage and children when life as they knew it was about to fundamentally change? On the other hand, if Jesus had been married, then what did that mean in practical terms for the fledgling church intent on emulating the man from Nazareth?

Traditionally the Jewish religion adhered to the commandment to be fruitful and multiply. However, even in the time of Jesus, there were exceptions. For example, the Jewish philosopher Philo described the Therapeutrides, a group of Jewish women who lived as celibates in an isolated community in Egypt with their male counterparts. They devoted their lives to prayer, studying the Torah, and composing hymns. At approximately the same time, the fledgling Christian community instituted the Order of Widows which provided a variety of women (whether previously married or widowed) with the opportunity to live independently of male supervision. Let’s just say that the early Jesus movement was faced with a diversity of cultural and social options not easily summarized in black and white terms.

As far as whether Jesus was actually married and his wife was Mary Magdalena, I’m still mulling over the evidence. In the early Christian literature contemporaneous with the canonical New Testament, several texts indicate that Jesus was married to Mary. Was this pure speculation or based on eyewitness accounts passed down through oral traditions? There might even be archaeological evidence for Jesus’ marital status in a burial chamber popularly known as the “Jesus Tomb” discovered in the Jerusalem suburb of Talpiot. Again, I’m sifting through the evidence in an attempt to come to an educated decision on the subject. One thing is certain: segments of the early Christian movement were convinced that Jesus did indeed have a wife and he considered her to be one of his disciples.

For Further Reading

Beasley, Jonathan – “Testing Indicates ‘Gospel of Jesus’s Wife’ Papyrus Fragment to be Ancient” – http://gospelofjesusswife.hds.harvard.edu/testing-indicates-gospel-jesuss-wife-papyrus-fragment-be-ancient

Goodstein, Laurie – “Papyrus Referring to Jesus’ Wife Is More Likely Ancient Than Fake, Scientists Say” The New York Times, April 10, 2014 (http://mobile.nytimes.com/2014/04/10/science/scrap-of-papyrus-referring-to-jesus-wife-is-likely-to-be-ancient-scientists-say.html?from=homepage)

Goodstein, Laurie – “Coptic Scholars Doubt and Hail a Reference to Jesus’ Wife” New York Times, Sept. 20, 2012. http://www.nytimes.com/2012/09/21/us/papyrus-fragment-that-refers-to-jesus-wife-stirs-debate.html

King, Karen L. – “‘Jesus said to them, ‘My wife…’ A New Coptic Papyrus Fragment.” Harvard Theological Review 107.2 (2014), 131-159.

King, Karen L. – “The Place of the Gospel of Philip in the Context of Early Christian Claims about Jesus’s Marital Status” New Testament Studies 59.4 (October 2013), 565-587. [http://www.hds.harvard.edu/sites/hds.harvard.edu/files/King_NTSOct2013_1.pdf]

Seim, Turid Karlsen – The Double Message: Patterns of Gender in Luke and Acts (Nashville: Abingdon, 1994)