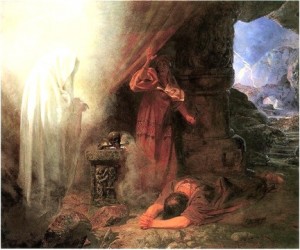

We learn in 1 Samuel 28:6 that the Lord is no longer communicating with King Saul through dreams, the Urim (a divinatory device), or prophets. So he seeks out a “Mistress of the Spirits” even though he has abolished witchcraft and personally persecuted its practitioners. In disguise and under the cover of darkness, Saul searches out a particular witch who resides in Endor. He asks her to bring forth the spirit of the prophet Samuel that he might receive information about God’s will.

“In the ancient Near East… necromancy is closely related to the worship of dead ancestors… The funerary cult had its counterpart in the belief that some illustrious ancestors of the familial clan (raised to the rank of family deities or quasi-deities) were granted after death supernatural powers, from which their lineage could benefit.” (Nihan pp.25-27)

Archeological remains confirm that pre-exilic Israelite culture included the worship of family ancestors. Though Samuel is not one of Saul’s ancestors, perhaps he felt a particular kinship with the prophet since he was the one to anoint him king. Another possibility is that the woman of Endor was herself a relative of Samuel. Saul spared her life and sought her out specifically because he knew she had special access to the prophet.

With little difficulty, it seams, the medium raises the wrathful spirit of Samuel who prophesizes that the next day Saul and his sons will die in battle. (Ironically Samuel argues that God cannot be compelled to reveal the future but then gives Saul the knowledge of the future that he seeks.) For all the illicitness of the profession of necromancy, it is interesting that Saul, his attendants and the medium herself never doubt that she has actually raised Samuel’s spirit nor do they doubt the divine authority of the prophet’s pronouncement. This raises some interesting questions.

“How does spirit possession or spirit divination differ from prophecy? The answer implied by 1 Samuel 28:6 would seem to be that there is no difference… One could seek an answer from God by various means. In every case, though, even with the Urim, God is being sought as the ultimate source of the answer. God communicates, but his medium may vary.” (Grabbe, p.139)

It is possible the witch subscribed to Yahwism but followed alternative channels of revelation? The rabbis hint at such a likelihood when they named her Zaphaniah, “god hides.”

Once the séance is completed, Saul collapsed on the floor as a result of dread and exhaustion. She quickly prepared bread and a freshly “sacrificed” calf and served it to the king.

“The cooking of food transforms her momentarily into a wifely character. Using the standard convention of a good woman soothing or nurturing a man with food, the author defuses the alarm of Samuel’s appearance and warning… The concrete nature of the hearth serves as a sign to remind the reader that the Medium is not a total outcast, but possesses the alimentary elements, bread and meat, of any civilized woman in the community.” (Bach, p.176)

We see her behaving like Abraham welcoming the guests at his tent with a meal of meat and bread. Her actions also echo the role of the Temple priests with their meal offerings, shew bread and animal sacrifices.”In a world in which only men could enter into the priesthood and in which men dominated the prophetic guilds, it is likely that women used other forms of divination to access the divine realm” (Kamionkowski, p.715). Being a witch was an opportunity for women to have a religious role in ancient Israel. Some scholars propose that like other divinatory techniques, necromancy was so commonly practiced in the pre-exilic period of Israel’s history that it was not prohibited initially. They base this conjecture on the fact that it is not mentioned in the earliest laws of Exodus 22:22-23:33. By the time of the later Holiness Codes of law (Lev. 22-26; and Lev. 19:31; 20:6-27) the practice was fully discredited as the priests attempted to gain exclusive religious authority.

Depicted as a gracious hostess, the storyteller’s sympathy is with the woman. Or is it? Pamela Reis argues that it is unrealistic to think that the terrified woman cares tenderly for the distraught king out of a sense of hospitality. After the séance, Saul no longer needs her powers and therefore he is potentially more dangerous. He might execute her to remove evidence of his hypocrisy. So she makes him a proposal. “Behold, your handmaid hearkened to your voice… Now you, too, listen to the voice of your maidservant. I will place before you a piece of bread so that you may eat, so that you may have strength when you go on your way” (vv.21-22). She wants him out of her house before he dies and she is implicated in his death.

“The witch’s proposition is expressed with intelligence, delicacy, and tact. The terms she set are obviously unequal… It is up to the king to correct the equation; he must make the mental computation and understand her to be actually saying: ‘I hearkened to you and set my life in your hand; now you hearken to me and set your life in my hand.'” (Reis, p.13)

With subtlety, she compares her life to a morsel of bread, not to denigrate herself but to negotiate with Saul. “Because of her willingness to risk her life for him, she has acquired a sort of right to his life.” (Simon, p.165) To seal the deal, Reis argues that she offers him raw meat with blood and sacred bread as a covenantal meal. By eating, Saul is contractually obligated to safeguard her life.

Even if the woman of Endor acts out of self-preservation, it seems that the narrator has great esteem for her. The author allows the medium to speak as much as Saul and Samuel do. The woman clearly states that Saul now must “listen to her voice” thus showing the dominance of her character. Furthermore, the narrator describes things from the witch’s point of view (“she saw he was very terrified” [v.21]) with the result that we have sympathy for her situation. In contrast, Samuel seems rather cold-hearted. “In leaving open the possibility of both altruism and self-interest, the narrative strengthens the depiction of the medium as a complex character.” (Reinhartz, p.69)

Are we seeing here a biblical respect for the kind of psychic powers the medium possesses? Or is the point of the story that King Saul’s depravity knew no bounds? It seems these readings are not mutually exclusive. Through the nuanced description of the witch we must ask ourselves what constitutes “proper” sources of divine communication. The story challenges us to ask ourselves how we can personally know the will of God.

For Further Reading

Ackerman, Susan – Under Every Green Tree: Popular Religion in Sixth-Century Judah (Eisenbrauns, 1992)

Bach, Alice – Women, Seduction, and Betrayal in Biblical Narrative (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997)

Brenner, Athalya – I Am: Biblical Women Tell Their Own Stories (Fortress Press, 2004)

Cogan, Mordechai – “The Road to En-Dor” in David P. Wright, David Noel Freedman and Avi Hurvirtz (eds.) Pomegranates and Golden Bells: Studies in Biblical, Jewish, and Near Eastern Ritual, Law, and Literature in Honor of Jacob Milgrom (Winona Lake, IN: Eisenbrauns, 1995)

Grabbe, Lester L. – Priests, Prophets, Diviners, Sages: A Socio- Historical Study of Religious Specialists in Ancient Israel (Trinity Press Int’l, 1995)

Jeffers, Ann – Magic and Divination in Ancient Palestine and Syria. Studies in the History of the Ancient Near East, V. 8. (Brill, 1996)

Kamionkowski, S. Tamar – “Holiness of the Land” in The Torah: A Women’s Commentary, Tamara Cohn Eskenazi and Andrea L. Weiss, eds. (URJ Press, 2007)

Nigosian, Solomon – Magic and Divination in the Old Testament (Sussex Academic Press, 2008)

Nihan, Christophe L. – “1 Samuel 28 and the Condemnation of Necromancy in Persian Yehud” in Todd E. Klutz, ed., Magic in the Biblical Worlds: From the Rod of Aaron to the Ring of Solomon (London/New York; T & T Clark, 2003)

Reinhartz, Adele – ‘Why Ask My Name?’ Anonymity and Identity in Biblical Narrative (New York: Oxford Univ. Press, 1998)

Reis, Pamela Tamarkin – “Eating the Blood: Saul and the Witch of Endor” in Journal for the Study of the Old Testament 73 (1997) 3-23.

Schmidt, Brian B. – “The ‘Witch’ of En-Dor, 1 Samuel 28, and Ancient Near Eastern Necromancy” in Marvin Meyer and Paul Mirecki, eds., Ancient Magic and Ritual Power. Religions in the Graeco-Roman World (Reprint), V. 129. (Humanities Press, 2001)

Schmidt, Brian B. – Israel’s Beneficent Dead: Ancestor Cult and Necromancy in Ancient Israelite Religion and Tradition (Eisenbrauns, 1996)

Simon, Uriel – “A Balanced Story: The Stern Prophet and the Kind Witch” Prooftexts 8 (1988) 164-65.