“There came out among the Israelites one whose mother was Israelite and whose father was Egyptian. And a fight broke out in the camp between that half Israelite and a certain Israelite. The son of the Israelite woman pronounced the Name in blasphemy, and he was brought to Moses-now his mother’s name was Shelomith daughter of Dibri of the tribe of Dan-and he was placed in custody, until the decision of the Lord should be made clear to them.” (Lev. 24:10-12)

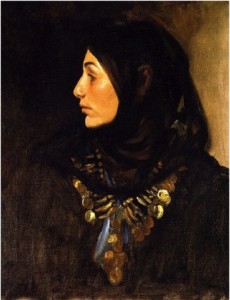

Everyone has heard of Shelomith. You know, the only named woman in Leviticus. She’s practically a household name. Ok, seriously. Of all the unnamed women with minor and pivotal roles, why is this one woman’s lineage and name given? In an unusual reversal in biblical narratives, her son and the father remain anonymous. Though Shelomith is named, in many ways she is anonymous for she does not speak or act. Her name then draws attention to the “hole” left in the story. We can’t help but wonder why she is mentioned. It is almost as if the text is inviting us to imagine the narrative from her point of view in order to find the missing pieces. What life experiences would lead a former Hebrew slave to give birth to a child by an Egyptian man? Was she raped or did she consent to the union? Did Shelomith and the Egyptian man marry? Perhaps he converted and followed his wife and son into the wilderness. Let’s look to the text to see if we can narrow down the possibilities.

First, the fact that the narrator notes her name leads us to think that she was a well-known woman.” It is possible, I believe, that she was actually a respected leader who helped people to feel at peace, and who would minister unto the people” (Lieber, p.236). Her lineage is also mentioned which adds further evidence that she was a prominent member of the community. She doesn’t seem to be shamed by her liaison with the Egyptian. If she had been raped, she would have been shunned for the rest of her life in the same way that King David’s daughter Tamar and Jacob’s daughter Dinah were. Furthermore, she would also need to be married to the Egyptian to retain her high standing.

Her son, the blasphemer, was eligible for citizenship (Deut. 23:8) and in the oldest Israelite laws, the so-called Covenant Code, it appears that the children of a marriage between an Israelite and an alien retained the mother’s status (see Exod 21:4 and Gruber, pp. 438-9). Note that there was no prohibition against intermarriage at this early stage of Israel’s history (Olyan, p.86).

Second, the text mentions that Shelomith was from the tribe of Dan which traces its origins back to Moses’ son Gershom (Judges 18:30).

The tribe “maintained its own altars, independent of the Levitical priests, for many years. The priests of Dan served the tribes of the northern kingdom, and did not follow the same rules as the Levitical priests in Judah… The presence of a rival priesthood and an alternative Jewish practice was intolerable for the descendants of Aaron.” (Lieber, p. 236)

Rabbi Lieber suggests that Shelomith’s son pronounced God’s name, perhaps as part of the Danite religious practices. This angered the Levite priesthood which claimed sole jurisdiction over the proper way in which to worship God.

“The Blasphemer’s utterance challenges the priestly monopoly over religious activity… In the biblical period, women who struggled for communal or social power were driven to find it outside of mainstream Judaism; they found themselves marginalized by ritual practice, laws or inheritance, and conventions of family life. Despite the struggle of some women, like Shilomit, for independence and influence, the priests managed to consolidate their control, and this text functions to warn women and others who might seek religious power that they would be punished severely.” (Lieber, pp. 236-7)

Perhaps Shelomith is mentioned specifically because she and her son were important members of the Danite cult.

Third, Shelomith’s name means peaceful. Gerstenberger suggests that, based on her name, we are to infer that her son’s behavior was not her fault. In the end, Shelomith must watch her son be stoned to death. Whether or not he was verbally aggressive against Yahweh or simply involved in alternative religious practices, we feel her pain and the irony of her peaceful name. I like to think that she continued to be well-received by her community despite the tragedy she faced.

For Further Reading

Bray, Jason Stephen – Sacred Dan: religious tradition and cultic practice in Judges 17-18. Library Hebrew Bible/Old Testament Studies. (T&T Clark, 2006)

Douglas, Mary – Leviticus as Literature (Oxford University Press, USA, 2001)

Gerstenberger, Erhard S. – Leviticus: A Commentary. Old Testament Library. (Westminster John Knox Press, 1996)

Gruber, Mayer I. – “Matrilineal Determination of Jewishness: Biblical and Near Eastern Roots” in Pomegranates and Golden Bells: Studies in Biblical, Jewish, and Near Eastern Ritual, Law, and Literature in Honor of Jacob Milgrom, David P. Wright, David Noel Freedman, Avi Hurvitz, eds. (Winona Lake, IN: Eisenbrauns, 1995) 437-443.

Lieber, Rabbi Valerie – “Elitism in the Levitical Priesthood” in The Women’s Torah Commentary, Rabbi Elyse Goldstein, ed. (URJ Press, 2007)

Olyan, Saul M. – Rites and Rank: Hierarchy in Biblical Representations of Cult (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2000)