“The king of Egypt spoke to the Hebrew midwives, one of whom was named Shiphrah and the other Puah, saying, ‘When you deliver the Hebrew women, look at the birthstool: if it is a boy, kill him; if it is a girl, let her live.’ The midwives, fearing God, did not do as the king of Egypt had told them; they let the boys live.” (Exodus 1:15-17)

Disturbed by the proliferation of the Hebrew people he had enslaved, the unnamed Pharaoh directed two named women to carry out a gendered genocide. By leaving him anonymous, the writer signals that the king is powerless and does not deserve to be named. As we shall see, the “midwives alone earn themselves a name by their conduct” (Siebert-Hommes, Let, pp. 113). Not only have Puah and Shiphrah been remembered throughout the generations, but the fact that they are actually named may indicate that they were national figures within Egyptian society.

But why does Pharaoh direct only newborn sons to be killed? The excuse he gives, “lest the people become numerous,” contradicts the motivation of a slave owner to increase the number of his slaves through a high birthrate. Many commentators note that Pharaoh must have assumed that by killing all the male Israelites, Egyptians would then marry the Hebrew females. Through the rules of patrilineal descent, the slave women would be subsumed into the ethnicity and culture of the Egyptians. Ironically, by emphatically demanding that the females live (Exod. 1:16,22), Pharaoh unwittingly participated in the flourishing of the Hebrew people.

Egyptian or Hebrew?

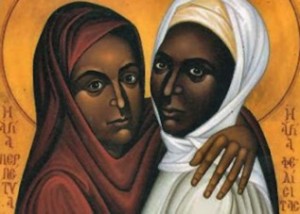

The text is ambiguous about whether the midwives were Hebrews or Egyptians.

“The consonantal Hebrew text, which is the form in which the story was preserved until vowels were added in the 7th century A.D., contains a description of the midwives which can be rendered either ‘to the Hebrew midwives’ or ‘to those midwiving the Hebrew women.’ Those who put the vowels into the text opted for the former interpretation, but many scholars argue that the story makes better sense if the midwives are Egyptians. How could Pharaoh trust Hebrew midwives to carry out such a commission against their own people…?” (Ackerman, pp.85-6).

Some of the oldest translations and interpreters such as the Septuagint, the Vulgate, Josephus and Abarbanel all considered the midwives to have been Egyptian.

Some argue that the midwives must have been Hebrew because they feared God. This presumes that only Hebrews had the moral fortitude to not murder helpless children or “fear the gods.” A better source of evidence lies in the midwives names “Shiphrah” and “Puah” which are Semitic, that is, of the same linguistic category as Hebrew. This does not constitute a conclusive argument since many Semitic people had immigrated to Egypt and were assimilated into all levels of society. If Puah and Shiphrah were Hebrews, then Pharaoh seemed naive in thinking he could rely on the women to carry out his orders. Taking a page from the Holocaust playbook, “Pharaoh does not suspect that the midwives will dare protect their own kind. He also knows that slavery crushes the spirit. He is counting on the demoralized Hebrew midwives to do anything to save themselves, even when it is at the expense of other Hebrews” (Ackerman, p.86). In his mind, the midwives had every reason to act violently against their own people.

Another option is that the midwives were Egyptian and Hebrew. “Given the length of time of the Hebrews’ sojourn in Egypt and the nature of their oppression, the nurse midwives could very well be interracial, part Hebrew and part Egyptian” (Gill, p.27). Perhaps the text is deliberately obscure on this point to draw our attention away from ethnicity to focus our attention on ethical issues which relate to all of humanity. This would be in keeping with the theme of the intergenerational, interfaith, and interracial collection of women who rescued the twelve tribes of Israel in Exodus 1 and 2.

Guild of Midwives

How could two midwives have assisted in all the births of the entire Hebrew people? Perhaps this story is a folk tradition that spread from a small locale served by two midwives. Then as their tale became legendary, Puah and Shiphrah became the “only” midwives among the Hebrew people.

“Shifra and Puah, are considered by Ibn Ezra [a 12th century C.E. Jewish commentator] to represent a large group of working midwives serving the population of Israelite women. They were perhaps the state fiscal administrators of the midwives’ guild” (Zornberg, p.67).

Meyers has conducted an extensive survey of Israelite woman’s organizations. Among other professions, ancient midwives formed guilds to transmit knowledge from one generation to the next. It appears that midwives were highly educated women.

“Egyptian and Babylonian texts from the third or second millennium BCE contain rules and procedures for attending childbirth and suggest that bodies of knowledge about gynecological and obstetrical practice were collected and transmitted in writing and probably also orally” (Meyers, Exodus, p.40).

Perhaps Shiphrah and Puah were the overseers of the guild (Goldstein, p.71). That the two women not only had direct contact with Pharaoh but also were sought out by the king of Egypt indicates that midwives were held in high esteem. Shiphrah and Puah may have held something akin to titles such as “Ministers of Population” or some such position within the government. From the narrator’s perspective and therefore the generations of Israelites who listened to the retelling, the midwives were perceived as holding powerful and prominent positions within Egypt.

One reason for their prominence may have been imbedded in the actual practices of ancient midwifery. Their procedures incorporated prayers, incantations and sacred rituals, thus making them part of the religious establishment.

“The practice of midwifery was situated in the magico-medical world…Because of the technical skills and religious functions of a woman dealing with the profound experience of bringing a new life into the world, a midwife was often called a ‘wise woman’ in ancient Near Eastern cultures…[in] English ‘midwife’ goes back to mid-wife, ‘knowing woman.’ Because they were believed to have the power to transform childbirth from a life-threatening experience to a joyful one, midwives were valued members of most societies until the advent of modern, male-dominated medicine” (Meyers, Exodus, pp.41-2).

Note that Shiphrah and Puah do not comply with Pharaoh’s commands because they “feared the God (lit. “ha-elohim“, the gods).” Faced with the prospect of fulfilling the Pharaoh’s horrific decree they chose to revere God and life at the risk of their own lives. “Pharaoh uses his power to kill, the midwives assist in bringing life into the world” (Siebert-Hommes, Let, p.25). This is how the midwives opposed the injustice of the status quo.

Midwives’ Rebellion

“Why have you done this thing, letting the boys live? The midwives answered Pharaoh, “Hebrew women are not like Egyptian women; they are vigorous [hayot] and give birth before the midwives arrive.” Exodus 1:17-19

The midwives, fearing God, did not do as the king of Egypt had told them; they let the boys live. Long before Moses and Aaron, the midwives stood before Pharaoh in defiance (Weems, p.32). The midwives engaged in what might be called civil disobedience. David Daube calls the midwives’ refusal “the oldest record in world literature of the spurning of a governmental decree” (p.5). By having direct contact with the king of Egypt, the women were overtly political (Setel, p.30).

Rather than cower before the most powerful man on earth they “defend themselves with straight faces against Pharaoh’s charge of insubordination. Their lives are at stake, and yet their sly comparison between the vigorous Hebrew women and the pampered Egyptians comes through as totally credible to the ‘wise’ king: ‘Oh yes, of course, that would be a problem, wouldn’t it?’ There is a great relish in this uneven conflict between the effete elite and the crude, but shrewd, vital, and resourceful, oppressed. The king fails to realize that not only is he being deceived, but he is also being mocked” (Ackerman, p.87).

In essence, Shiphrah and Puah insinuated that the Hebrew women were strong in comparison to weak Egyptian women.

Lively Women: Hebrew Women are Life Producers

“The midwives answered Pharaoh, ‘Hebrew women are not like Egyptian women; they are vigorous [hayot] and give birth before the midwives arrive.'” Exodus 1:19

Typically hayot is interpreted to mean that the Hebrew women were like animals and therefore not really in need of midwives. “The implication is that these women are born to breed. That is what–perhaps all–they are good for. Consequently, they deliver before the midwife can arrive. How can Pharaoh argue with information that confirms his suspicions of the Hebrews’ difference?” (Fewell/Gunn, p.92). The midwives exploited the king’s prejudices for their own purposes.

However, as satisfying as it is to think of the midwives out-foxing Pharaoh, Siebert-Hommes has concluded after an exhaustive linguistic analysis of hayot that literally the word means “life producers.” The term does not appear to hold any connotation that the Hebrew women were being compared to beasts. Rather, the women were compared to life itself. They “are life producers and thereby sustain the history of the ‘Elohim of life’…The conclusion forces itself upon us that the text is not primarily communicating about a quick delivery, in which the help of midwives is superfluous” (Siebert-Hommes, Let, p. 108). In the narrative Pharaoh spoke as if he had command over life and death. However it is the women who have control over life. Pharaoh can’t rid himself of the Hebrews because the life of their nation is in the women.

Feminist Issues

Several feminist scholars maintain that regardless of the accomplishments of Puah and Shifrah, we shouldn’t get too excited about them. They were nothing more than the weakest of the weak, submissive women kowtowing to their male superior, staying within traditional gender boundaries that were never challenged or subverted by the narrative. The women are not valued for any of their inherent characteristics. Here’s an example of this line of thought:

“They care for and save babies, the proper tasks for women in an androcentric perspective. Although the narrative stresses their significance, they do not cross gender-specific roles. As long as they act according to these roles, the androcentric storyteller allows them even to outwit the Egyptian king…The unusual emphasis on the women allows the storyteller to characterize the pharaoh as particularly despicable; he is foolish enough to be tricked by women” (Scholz, p.24).

Being tricked by men who are assumed to be powerful would not demonstrate God’s supremacy over Pharaoh as sufficiently as lowly women deceiving the king of Egypt. The consequence of this line of reasoning is that we shouldn’t look to the midwives as models for liberation. Underlying this argument is the belief that women are automatically pawns of patriarchy if they give birth to male children and assist other women in giving birth to sons. In this male oriented tale, they argue. The “women are only concerned about male infants and one male infant in particular…After the days of childcare and special support for Moses are over, women disappear from the story” (Scholz, pp. 25-6). This is not the belief of the narrator who introduced female after female vital to the salvation of the Hebrew people.

The enemy of justice wanted to kill all the male babies because he thought females were insignificant. By holding up the women as heroes, the narrator makes it clear he/she stands in opposition to Pharaoh’s conception of the inferiority of women. When Pharaoh told them to kill the boys, they insisted on saving all the children, regardless of gender. Rather than being the means to an end, the midwives were heroines in their own right. The narrator invites the reader to resist Pharaoh’s sexist ideology, to not buy into his twisted logic. In short, I think it is erroneous to presume that the midwives allowed themselves to be exploited by men in any way or that the narrator should be blamed for perpetuating an oppressive ideology.

Pharaoh’s Final Solution

“Every son that is born you shall throw into the Nile, but you shall let every girl live!” (Exodus 1:22).

Pharaoh couldn’t count on the midwives to carry out his orders so he enlisted the fears of his people. Note that Pharaoh did not specify that only Hebrew sons were to be killed. “It is clear from the context that only the offspring of the Israelites can be intended here. However, just as in v. 10, there is a deliberate ambiguity in the formulation. When Israel departs from the land, in truth the last plague will strike every son, this time of the Egyptians (12:29). The whole people, each and every one of them, is now responsible for the extermination” (Fischer, pp. 117-8). Fischer then relates Pharaoh’s command to the Holocaust era Nurnberg race laws where fear of surveillance and denunciation compelled the citizens to comply with the extreme edicts. In contrast to the Germans, the midwives challenged Pharaoh’s assumption that they were too weak to resist his orders.

Their Houses

“And God dealt well with the midwives; and the people multiplied and increased greatly. And because the midwives feared God, He established households for them.” (Exodus 1:20-21)

Rashi, quoting the midrash, states that these houses refer to God’s gift of dynasties of kings and priests. Because of their actions, the Hebrew community continued to flourish and so the midwives were rewarded with prosperous families themselves. In “this female-centered text, the identification of households is with women, as it is in several other female-centered biblical texts, rather than with the men” (Meyers, Exodus, p.37). According to Meyers’ research, it appears that bet ’em (mother’s house) is “a technical term that serves as a counterpart to the far more common bet ‘ab… ‘house of the father,’ [which] involves both spatial/material and kinship/lineage concerns.” (Meyer, To Her Mother’s, pp.40-1). Like the house of the father, the house of the mother served “as the basic economic unit, producing virtually all of what was needed for the subsistence of its members” (ibid. p.41). Like the father’s house, the mother’s household provided not only shelter but encompassed economic production, social activity, and religious activities. In this social unit, the matriarch dominated daily affairs and family decisions. The stories of Rahab, Rebecca, Ruth, and the Song of Songs are other examples of the institution of the mother’s house in ancient Israel.

Conclusion

In our own time, I can imagine anti-immigration proponents quoting Pharaoh: “Come, let us deal shrewdly with them! They have become a people numerous and powerful…”

“The prejudices directed at [the Hebrew people] are the same as those that fall on the poor, foreigners, and refugees today: they have too many children, they are lazy, and some day they may dilute our own people so much that they could take advantage of a national crisis and gain control” (Fischer, p.115).

Not only are Shiphrah and Puah models of how women bonding together can be “freedom fighters” against an oppressive system, but more generally “the text moves beyond nationalistic concerns to bear witness to the power of faith to transcend ethnic boundaries” (Exum, p.48-9). We have an opportunity in our own time to speak out against injustice just as the midwives did thousands of years ago. And the midwives demonstrated, it doesn’t matter how few our numbers. Each individual counts in the fight for justice and liberation.

For Further Reading

Ackerman, James S. – “The Literary Context of the Moses Birth Story (Exodus 1-2)” in Gros Louis, Kenneth R.R., with Ackerman, James S., and Warshaw, Thayer S., eds., Literary Interpretations of Biblical Narratives. The Bible in literature courses. (Abingdon, 1974)

Cohen, Jonathan – The Origins and Evolution of the Moses Nativity Story (Leiden: Brill, 1993)

Daube, David – Civil Disobedience in Antiquity (Edinburgh: University Press, 1972)

Exum, J. Cheryl – “‘You Shall Let Every Daughter Live’: A Study of Exodus 1:8-2:10” in A Feminist Companion to Exodus to Deuteronomy, (Series 1), Athalya Brenner, ed. Feminist Companion to the Bible 6. (Sheffield, Eng.: Sheffield Academic Press, 1994)

Fewell, Danna Nolan and David M. Gunn – Gender, Power, and Promise: The Subject of the Bible’s First Story (Nashville: Abingdon Press, 1993)

Fischer, Irmtraud – Women Who Wrestled with God: Biblical Stories of Israel’s Beginnings. Linda M. Maloney, trans. (Collegeville, Minn.: Liturgical, 2005)

Fuchs, Esther – “A Jewish-Feminist Reading of Exodus 1-2” in Jews, Christians, and the Theology of the Hebrew Scriptures, Alice Ogden Bellis and Joel S. Kaminsky, eds. Society for Biblical Literature Symposium Series 8. (Atlanta: Society of Biblical Literature, 2000) 307-26.

Gill, Laverne McCain – Vashti’s Victory: And Other Biblical Women Resisting Injustice (Pilgrim Press, 2003)

Goldstein, Elyse – ReVisions: Seeing Torah Through a Feminist Lens (Woodstock, Vermont: Jewish Lights Publishing, 1998)

Lapsley, Jacqueline E. – Whispering the Word: Hearing Women’s Stories in the Old Testament (Louisville: Westminster John Knox, 2005)

Meyers, Carol L. – Exodus. New Cambridge Bible Commentary. (Cambridge University Press, 2005)

Meyers, Carol L. – “‘To Her Mother’s House’: Considering a Counterpart to the Israelite Bet ab” in The Bible and the Politics of Exegesis: Essays in Honor of Norman K. Gottwald, David Jobling, Peggy L. Day, and Gerald T. Sheppard (Cleveland: Pilgrim, 1991) 39-51.

Paul, Shalom M. – “Exodus 1:21: ‘To Found a Family’ – A Biblical and Akkadian Idiom'” Maarav 8 (1992), 139-42.

Scholz, Susanne – “The Complexities of ‘His’ Liberation Talk: A Literary Feminist Reading of the Book of Exodus” in A Feminist Companion to Samuel and Kings, 1st series. Feminist Companion to the Bible 5. Athalya Brenner, ed. (Sheffield, Eng.: Sheffield Academic Press, 1994)

Setel, T. Drorah – “Exodus,” in The Women’s Bible Commentary, Carol A. Newsom and Sharon H. Ringe, eds. (Louisville: Westminster John Knox, 1992)

Siebert-Hommes, Jopie C. – “But if She Be a Daughter… She May Live! ‘Daughters’ and ‘Sons’ in Exodus 1-2” in A Feminist Companion to Exodus to Deuteronomy, Athalya Brenner, ed.

Siebert-Hommes, Jopie C. – Let the Daughters Live! The Literary Architecture of Exodus 1-2 As a Key for Interpretation. Biblical Interpretation Series 37. (Brill, 1999)

Weems, Renita J. – “The Hebrew Women Are Not Like the Egyptian Women: The Ideology of Race, Gender and Sexual Reproduction in Exodus 1” Semeia 59 (1992) 25-34.

Zornberg, Avivah Gottlieb – The Particulars of Rapture: Reflections on Exodus (Image, 2002)