I’ve been asked if there is any historical or archaeological evidence for Junia’s ministry and life. On a strictly scientific basis, no. Based on the standards of plausibility, we might have something to work with. We can’t identify Junia as a historical person outside of her mention by Paul in Romans 16:7. However, if Junia was the same person as Joanna mentioned by Luke in (cf. Luke 8:3 and Luke 24:10), then there is a possibility that she might have been a historical figure. So let me begin by explaining why there is a probability that Junia = Joanna.

Paul describes Junia as “in Christ before I was.” In other words, she believed that Jesus was the Messiah before Paul was converted to the same idea on the road to Damascus in approximately 34 C.E., just after Jesus died. Junia then, would have been, at the very latest, a member of the band of disciples awaiting the Messiah’s return, probably in Jerusalem. Since the writer of Luke tells us that Joanna was an eyewitness of Jesus’ death and resurrection, this places Junia and Joanna in close proximity in time and perhaps place.

Paul also described Junia as an “apostle among the apostles” by which he means that she was well known among the members of the apostolic body. (For many decades there has been a great deal of debate over whether Junia was a woman’s name and how the phrase “apostle among the apostles” should be translated. Currently it is widely accepted in the scholarly community that Junia was a woman and that she was indeed a prominent apostle.) Paul uses the term “apostle” in a broader sense than that of Matthew, Mark and Luke who use the term to refer to the “twelve.” Other wise, how could he consider himself an apostle? By the term, he meant someone who had been commissioned by the risen Jesus to spread the Gospel. Paul also emphasized that he was the last of the apostles (1 Cor. 15:9; cf. 9:1). Once again we learn that according to Paul, Junia was an apostle before 34 C.E. and she was commissioned personally by Jesus. As an eyewitness to the crucifixion and resurrection, according to Luke, Joanna matches this description perfectly.

It turns out that the name Joanna (Hebrew: Yehohanah) would have been pronounced “Junia” in Latin. Those within the sphere of the Herodians would have been known by their Latin names. However, in humbler settings (such as traveling on the road with an itinerant preacher?), few Palestinian Jews would have wanted to use a name that “proclaimed allegiance to Rome” (Bauchman, p. 182). Thus, if Joanna/Junia was a historical person, she would have used both names in different settlings, especially since the two names were audibly equivalent.

Based on these observations, I feel confident in equating Joanna and Junia as the same person. So if we can find epigraphic, textual or archaeological evidence supporting the historicity of Joanna, then we will have also found evidence for the authenticity of Junia.

The trail starts with the ossuary of Yehohanah brought to my attention by my friend Robin Jones. Ossuaries are Jewish secondary burial containers commonly found in Jerusalem dating from 100 B.C.E. to 100 C.E. By their very definition, ossuaries can be dated to a fairly narrow timeframe which includes the time of Jesus and the nascent Christian church.

Previously I’ve briefly mentioned that the ossuary of Yehohanah, granddaughter of the High Priest Theophilus, might be the burial box of Joanna mentioned in Luke. The Israeli Department of Antiquities acquired the box in 1984. As Professor Mykytiuk noted in my discussion regarding Jezebel’s seal, “Of course, it is risky to buy anything on the antiquities market… if an item is of unknown origin (provenance) it cannot be used to draw conclusions. It could be a forgery or a fake.” As far as I know, the authenticity of the Yehohanah’s ossuary has not been questioned, so the possibility that this stone box might be the final resting place of the Joanna noted in Luke’s gospel is not impossible, just not archaeologically verifiable.

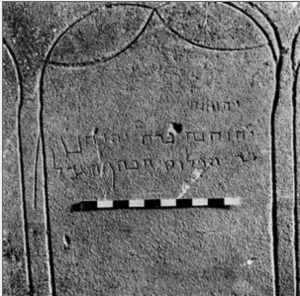

Inscribed on the front of the ossuary were the following words written in Aramaic (the everyday language of Judea at the time):

“Yehohanah

Yehohanah daughter of Yehohanan

Son of Theophilus the high priest”

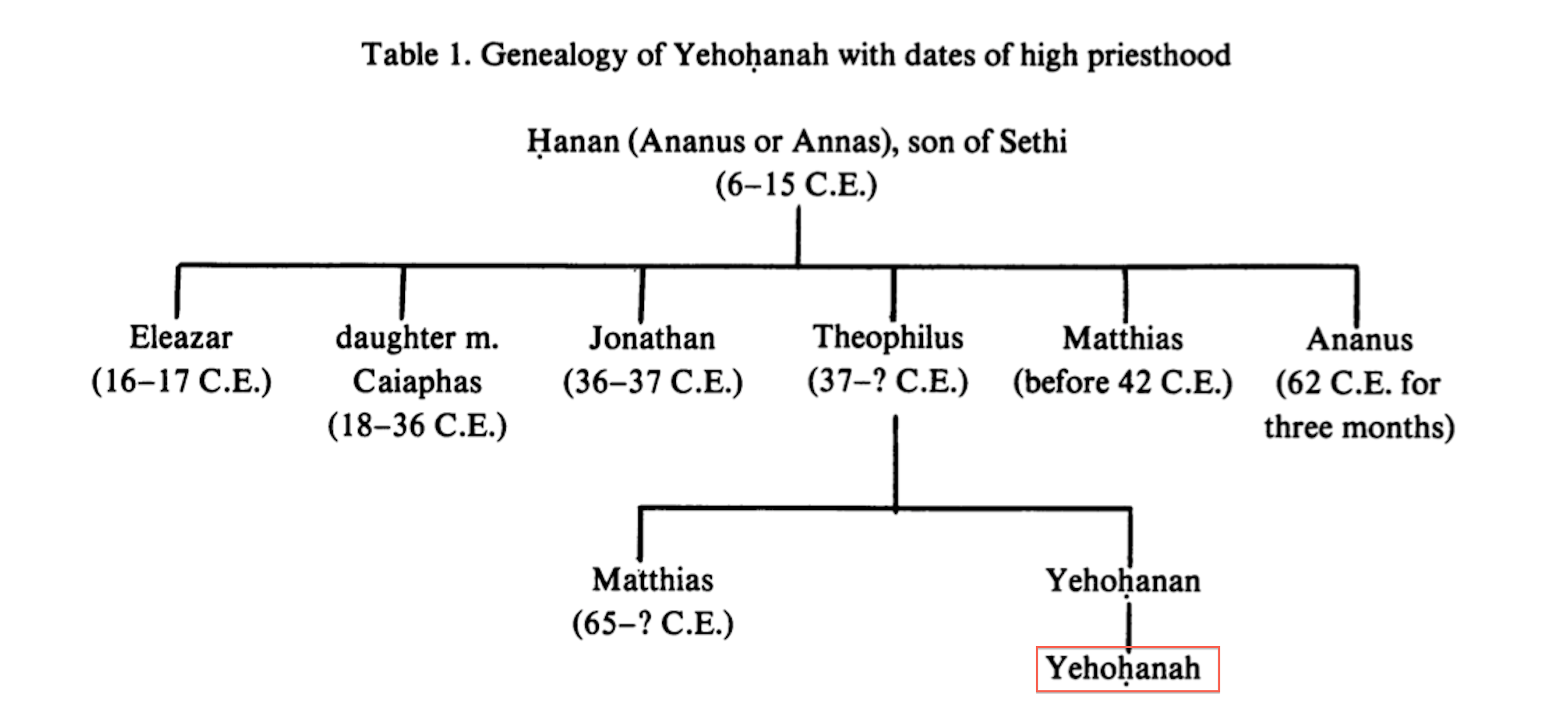

For quick reference here is the genealogy of Yohahanah’s family as depicted by Barag and Flusser:

As you can see, Yohahanah was related by marriage to Caiaphas, the high priest involved in Jesus’ conviction.

So what are the chances that this Yohahanah is the Joanna of the New Testament? Using Tal Ilan’s study of all known Jewish women’s names from 330 BCE to 200 CE in Palestine, we discover that there are eight occurrences of the name Joanna (aka Johanna), making it the fifth most common name at that time. For the purposes of making sound historical identifications, Professor Ilan established the following criteria:

1) If the person is mentioned in a dated document, there can be no discrepancy in chronology. In other words, if the document says that so and so lived in first century C.E., the historical person with the same name must also have lived at that time.

2) If both the historically established person and the person of the same name under question are from the same geographic area, the certainty of the identification is increased.

3) Just because someone has the same name as a historical person, it doesn’t mean that they are identical. However, if the name is rare, if the title of both entities are given and the family names match, it is more likely that a correspondence can be found between the two names.

Not all of these criteria must be met for a solid identification to be made, but the more boxes that can be ticked on this list, the more certain the proof of identity. In the case of Joanna, both the chronology and geography of Joanna of the Gospel of Luke and the Yohahanah of the ossuary match.

In addition, the Gospel of Luke was dedicated to an unidentified Theophilus, a rare Jewish name according to Ilan’s research.

“…when the two name combination of Johanna and Theophilus appearing together on the ossuary and also appearing together in the Gospel of Luke (and only in the Gospel of Luke) when considered together with the rarity of the Theophilus name in Palestine is strong circumstantial evidence that the proposed identification is correct.” (Anderson, Kindle Locations 694-698)

The writer of Luke addresses his intended audience as “most excellent Theophilus,” a title or designation consistent when referring to a high priest of the Jerusalem temple. “Thus, the conclusion that Luke is addressing ‘most excellent Theophilus,’ the High Priest, is warranted.” (Anderson, Kindle Location 706-707).

In addition, only the wealthy could afford burial in an individual ossuary (Tzaferis, p. 30). As the wife of Herod Antipas’ right hand man responsible for the tetrarch’s financial affairs and all of his properties, Joanna and her husband belonged to the wealthy retainer class of a royal household (Hoehner, p. 304). “Thus, the facts establish both Johanna, the granddaughter of the High Priest, and Johanna, wife of Chuza, are persons of means” (Anderson, Kindle Locations 753-754).

So I have to ask myself, what are the chances that all of these markers of identity are just coincidences? For historians, the bridge between the ossuary and the Gospel of Luke can’t be crossed with certainty. But for the historical fiction writer intent on probability and plausibility, the bridge is sturdy enough for me.

For Further Reading

Anderson, Richard – “Theophilus: a Proposal [as to his identity in Luke 1:3 and Acts 1:1],” The Evangelical Quarterly 69.3 (July-Sept. 1997): 195-215.

Anderson, Richard – Who are Johanna and Theophilus?: The Irony of the Intended Audience of the Gospel of Luke. Kindle Edition, 2010.

Barag, D. and D. Flusser – “The Ossuary of Yehohanah Granddaughter of the High Priest Theophilus”, Israel Exploration Journal, 36 (1986), 39-44.

Hoehner, Harold W., – Herod Antipas, (Cambridge [Eng., University Press, 1972).

Ilan, Tal, A Lexicon of Jewish Names in Late Antiquity: Part I: Palestine 330 BCE-200 CE, (Tübingen: Mohr-Siebeck, 2002).

Tzaferis, V., “Jewish Tombs at and near Giv’at ha-Mivatar, Jerusalem,” Israel Exploration Journal 20 (1970) 18-32.

2 thoughts on “Was Junia a Historical Person?”

Comments are closed.