“And Jacob said to Joseph, “El Shaddai appeared to me at Luz in the land of Canaan, and He blessed me, and said to me, ‘I will make you fertile and numerous…’ And Shaddai who blesses you…blessings of the breast and womb.” Genesis 48:3-4; 49:25

“God also spoke to Moses and said to him: ‘I am the Lord. I appeared to Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob as El Shaddai, but I did not make Myself known to them by my name Yahweh.” Exodus 6:3

God of the Patriarchs and Matriarchs

Rooted in a very old poetic tradition, the divine name Shaddai occurs 48 times in the Hebrew Bible and has traditionally been translated as Almighty. The early Hebrew ancestors of Israel “worshipped the supreme god under various appellations, such as El (as among the North Canaanites of Ugarit), (El-) ‘Elyon, (El-) Saddai” (Albright, p.191). Perhaps the deity’s name is related to Shaddai, a late Bronze Age Amorite city on the banks of the Euphrates River (in what is now northern Syria). It has been surmised that Shaddai was the god worshipped in this area, an area associated with Abraham’s home. It is “quite reasonable to suppose that the ancestors of the Hebrew brought it [Shaddai] with them from northwestern Mesopotamia to Palestine” (Albright, p.193). The early patriarchs and matriarchs then would have perceived Shaddai as their chief god.

In the sections of the Bible believed to have been written by priests (“P”) who incorporated ancient stories, Shaddai is always the name of the God of the Patriarchs, the God of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob, the God whose name was changed to Yahweh in the time of Moses. “The theophany of Sinai then represents the end of the domination of the Shaddai concept and the beginning of the rule of Yahweh” (Albright, p.193). One of the objectives of the priestly source P was to assimilate into Yahweh all of the patriarchal gods, including the Canaanite El, hence the compound name El Shaddai.

Proposed Etymologies

Prior to modern scholarship, Shaddai was believed to be derived from “to devastate.” However, Albright in his thorough investigation on the subject writes:

“Unhappily for the plausibility of this view, the only known word from which it could be directly derived, is sod, ‘devastation,’ so that that it could at best mean only ‘belonging to devastation,’ or the like. The adjectival formation in question is not Hebrew at all…so the difficulty becomes still greater” (p.181).

Other scholars suggested Shaddai was derived from the Arabic sayyid, meaning “lord,” which came to mean “demon.” Though Hebrew predated Arabic, it is thought that the Arabic retained a stem lost in Hebrew. However this proposition has been ruled out by more recent studies.

Modern scholarship identifies Shaddai with the Akkadian word sadu, “mountain.” Again, Albright cautions us: “A direct identification is, however, hardly possible because of fatal phonetic obstacles” (p.183). Biale contends that if El Shaddai was thought of as a mountain deity, then “why is he not attached to any specific mountainous sanctuary in the biblical texts?… Some have suggested that the utter lack of location characteristic of El Shaddai is simply a result of the Priestly theology in which God is universal” (pp.242-3). Certainly Shaddai was never connected to specific mountains such as Yahweh’s Sinai, Horeb, Zion and Moriah.

Albright suggests, along with other scholars, that Shaddai is derived more directly from the Hebrew word shadayim, “breasts” which in turn was derived from the Akkadian shadu, “breast.” This semantic possibility does not preclude the connection to mountainous heights. “Words for ‘breast’ often develop the meaning ‘elevation, mound, hill, mountain’; mountains shaped somewhat like breasts are frequently called ‘breast, two breasts’ in Arabic” (Albright, p.184). In fact immediately following Jacob’s blessing of breasts (Gen.48:3-4; 49:25) the text speaks of the blessings of ancient mountains; bounty of everlasting hills.

Biale also notes that in Egyptian, shdi is a verb meaning “to suckle” which would make El Shaddai the God who suckles. “Whether derived from Akkadian or Egyptian, the God with breasts is a natural interpretation of the fertility deity in Genesis” (Biale, p.249). Most of the biblical passages mentioning El Shaddai depict the deity as a fertility god giving blessings for ample progeny. In Genesis 49:25 we have a striking wordplay on the name Shaddai with the blessings of the breasts (shadayim). Along with the wordplay on Shaddai and shadayim “breasts”, Genesis 49’s use of rehem “womb” may also allude to a divinity by the name of Rahmay, “the one of the womb” (Lutzky, p.24). Certainly the Torah connects God with gifts of fertility and fruitfulness.

The Consort of El?

Chronologically El Shaddai appears in the texts after the earlier usage of the plural gods Elohim and before the single god Yahweh. Many scholars have speculated that El Shaddai represents the mid-point of the evolutionary process from polytheism to monotheism. Throughout the Near East, there was a tendency to merge gods with similar traits and functions. “A minor deity, worshipped by a small group of adherents, may become popular and merge with a great deity” (Cross, p.49). This appears to be the case with the syncretistic impulse behind the combination of El and Shaddai. “The placement of the compound divine name between plural and singular gods suggests a duel, two deities, shared by the early Israelites and their neighbors” (Lutzky, p.35). The compound names often signified that the two deities might have shared a temple, had similar features or were consorts. “If Shadday was a goddess epithet, then she might have been the consort of El” (Lutzky, pp.32-3). The combination of El and Shaddai represents an androgynous way of thinking about God. The concept of El Shaddai includes the truth that both male and female are created in the image of God.

Typically Asherah was depicted as El’s consort and carried the fertility functions of the immortal couple. “Hence, it is possible that, just as El was assimilated to Yahweh, so Asherah was adopted into Priestly Yahwism by a surreptitious sex change: the Canaanite ‘wet nurse of the gods’ was reincarnated as El Shaddai, the God with breasts” (Biale, p.254). Shaddai would then be a demythologization of El, the Canaanite father god and his consort Asherah. The priestly writer seems to have elevated El Shaddai rather than call attention to the worship of the goddess. The verse notifying Moses that Yahweh appeared to Abraham, Isaac and Jacob as El Shaddai (Exod. 6:3) “may thus inadvertently reveal, in disguised form, a faithful image of the religion of early Israel, namely, the worship of El and Shadday (El and Asherah)” (Lutzky, p.35).

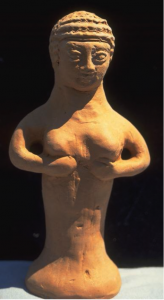

It should be noted that archaeology has found evidence that Asherah was the female consort of Yahweh, particularly in the inscriptions found at Kuntillet ‘Ajrud in the Sinai which records blessings to YHWH and to his Asherah. As Biale concludes, “there is abundant evidence that the fertility tradition of El Shaddai may have originated with the Israelite interest in the figure of Asherah, the fertility goddess represented by breasts” (p.254). Incidentally, Asherah is usually depicted with prominent breasts, which she holds up as if to provide the world nourishment.

The God of Ezekiel, Ruth and Job

At the time of the writing of the books of Ezekiel, Ruth and Job, Shaddai had acquired the image of a storm and war god, the same symbolism used to describe Yahweh in the exilic and post-exilic period. After the loss of the Temple and the forced exile to Babylon, the Israelites searched for a reason for their troubles. The post-exilic authors came to the conclusion that an all-powerful God was punishing them for their sins. This is particularly clear in Job where Shaddai is malevolent: “For Shaddai’s barbs pierce me” (Job 6:4). See also Ruth 1:20: “for Shaddai has embittered me” (Ruth 1:20).

“Hence, in the late texts, Shaddai–used as a substitute for Yahweh–has the associations common to late Israelite theology: awe and veneration at best, fear and hostility at worst” (Biale, p.246).

In an attempt to appear archaic, these late texts revived the popularity of Shaddai after it had been abandoned for some time.

The God Who Feeds

The Bible is replete with descriptions of God as nurturer, most famously as the deity that provided manna for Israel in the wilderness.

“A baby drinks every day from the mother’s breast, which completely satisfies his or her nutritional needs. Similarly, every day Israel had enough manna to eat in the wilderness and was completely dependent on God’s protection. What better way to express this absolute reliance on God for food than the relationship of a child with his or her mother?” (Claassens, p.2).

Like mother’s milk, the leftover manna quickly spoiled thereby preventing the Children of Israel from storing manna. Israel’s only option was to trust God fully.

In an overfed consumer society within a world where millions experience starvation, the distribution of manna equally to all sets an example for social equity. The deeper symbolism of the manna episode encourages us to exhibit the same measures of justice and fairness. The conception of God who equitably measures out food to everyone calls on us to feed the hungry. The metaphor of God with breasts should urge us to demand adequate food supply for all people.

“This metaphor of God as the Mother who feeds can thus be described as a living metaphor…Some people may be shocked by this metaphor, as they are not used to thinking about God in this way. This may exactly be where the power of this metaphor lies…thereby moving them toward a new understanding concerning God and their relationship with God” (Claassens, p.22).

Compelling metaphors can change the way we think, as well as the way we act. Inclusive images like the God with breasts have the power to enrich our relationship with the divine and clarify our role in the world.

For Further Reading

Albright, William Foxwell – “The Names Shaddai and Abram” Journal of Biblical Literature 54 (1935) 180-93.

Biale, David – “The God with Breasts: El-Shaddai in the Bible” History of Religions 21: 3 (Feb. 1982) 240-56.

Claassens, L. J. M. – The God Who Provides: Biblical Images of Divine Nourishment (Nashville, TN: Abingdon Press, 2004)

Cross, Frank Moore – Canaanite Myth & Hebrew Epic: Essays in the History of the Religion of Israel (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1973)

Lutzky, Harriet C. – “Shadday as a Goddess Epithet,” Vetus Testamentum 48 (1998), 15-36.

Mollenkott, Virginia Ramey – The Divine Feminine: The Biblical Imagery of God as Female (New York: Crossroad, 1988)