A week before beginning to move back to the States from Italy, I met the other Jew of Brindisi at a party. I’ve lived here two years and just before I leave, I find someone I could have celebrated the holidays with?! Her name is Syd and she’s an American expat who has lived here for eons with her Italian husband and children. We immediately got along. In the short time we spoke at the party, we couldn’t talk quickly enough to learn about each other. In that initial conversation, she mentioned that there was a medieval mikvah (Jewish ritual bath) and remains of a synagogue in the nearby town of Lecce. I couldn’t believe it. I have three guidebooks about Jewish Italian history and not one of them mentioned Lecce. The only ancient Italian mikvah I knew was in Sicily. I have a long abiding interest in mikvot since writing Judith: Wise Woman of Bethulia because the ancient biblical heroine was known for her ritual purification washings. So when Syd offered to show me the ancient Italian site, I dropped all my packing and we drove to Lecce.

We were met by Giuseppe Pagliare, a scholar of the Jewish history of Lecce. About a year earlier Syd had discovered him and his work. We were lucky he was available on such short notice to guide us through the old Jewish quarter of the city. Though he is not a “member of the tribe,” Giuseppe is passionate about all things Jewish—he even goes by the Hebrew nickname of Yossi.

He explained that Lecce, like many ancient cities, is built in layers. With the passing centuries, each new generation built on top of the prior so the oldest part of the city is buried under what we see today. After the Jews of Italy were expelled for the last time in 1541, Lecce grew over the old quarter where they had lived. When new maps were drawn, no trace of the former community remained on record. In time, Jewish existence in Lecce was forgotten leaving behind only a street named Via della Sinagoga (“street of the synagogue”) and a handful of legends. These small crumbs of evidence led contemporary historians to seek out the presence of a Jewish community near Via della Sinagoga.

The first breakthrough came in 1994 with the renovation of the Palazzo Adorno just down the street from the church of Santa Croce, the highlight of the baroque architecture of Lecce. Underneath the Palazzo they discovered two entrances and a complex of rooms “like a city,” Giuseppe said. The various rooms surrounding the mikvah were probably used for a study house and other community related activities. Since the site is not open to the public, Giuseppe made arrangements to take us down into the area now used as a very messy archive. It was here that they broke down a wall in 1994 and uncovered what was later determined to be steps leading down to a large mikvah dating to the time before Jews were expelled for the last time in 1541. I took a picture of a fish swimming in the fresh water.

Since the last time Giuseppe visited the site, he learned that most mikvot at the time were designed with at least two pools, one for women and one for men. So this time, armed with the flashlight I’d brought with me, Giuseppe searched for any indication of another ritual bath. In one of the disorganized rooms, between rusting metal cabinets, we found a grating and peered down into the dark. We saw water below and an inlet channel typical of a mikvah which allows the proper amount of fresh water into the pool for ritual purposes. Of course we couldn’t be sure it was the second mikvah, but given Giuseppe’s experience and knowledge, he said it definitely wasn’t a well. Needless to say, we were excited about the possibility of finding an unrecorded ancient mikvah. I was feeling a little like Indiana Jones at that point!

Giuseppe also showed us a stone inscribed with Hebrew which I believe said “bait le ohavei hael” (House for God Lovers). This stone originally identified the local synagogue or the aron kodesh, the place where a synagogue’s Torah scrolls are kept. The stone is lodged upside down in an alcove, just where it had been placed next to the sewer line centuries ago. I bent down and turned up to take a picture of the neatly chiseled Hebrew words. Giuseppe explained that after being removed from it original position in the synagogue, the inscribed stone was purposefully placed next to the sewer to offend the Jews, a common practice in the Middle Ages during times of Jewish persecution. Apparently, this inscribed stone is the only holy writing that remains from any synagogue in Salento (southern Italy), a region once scattered with a number of Jewish communities. Most of these communities, Giuseppe explained, were located near the sea so that in times of increased anti-Semitism, Jews could escape quickly via ships in the harbor.

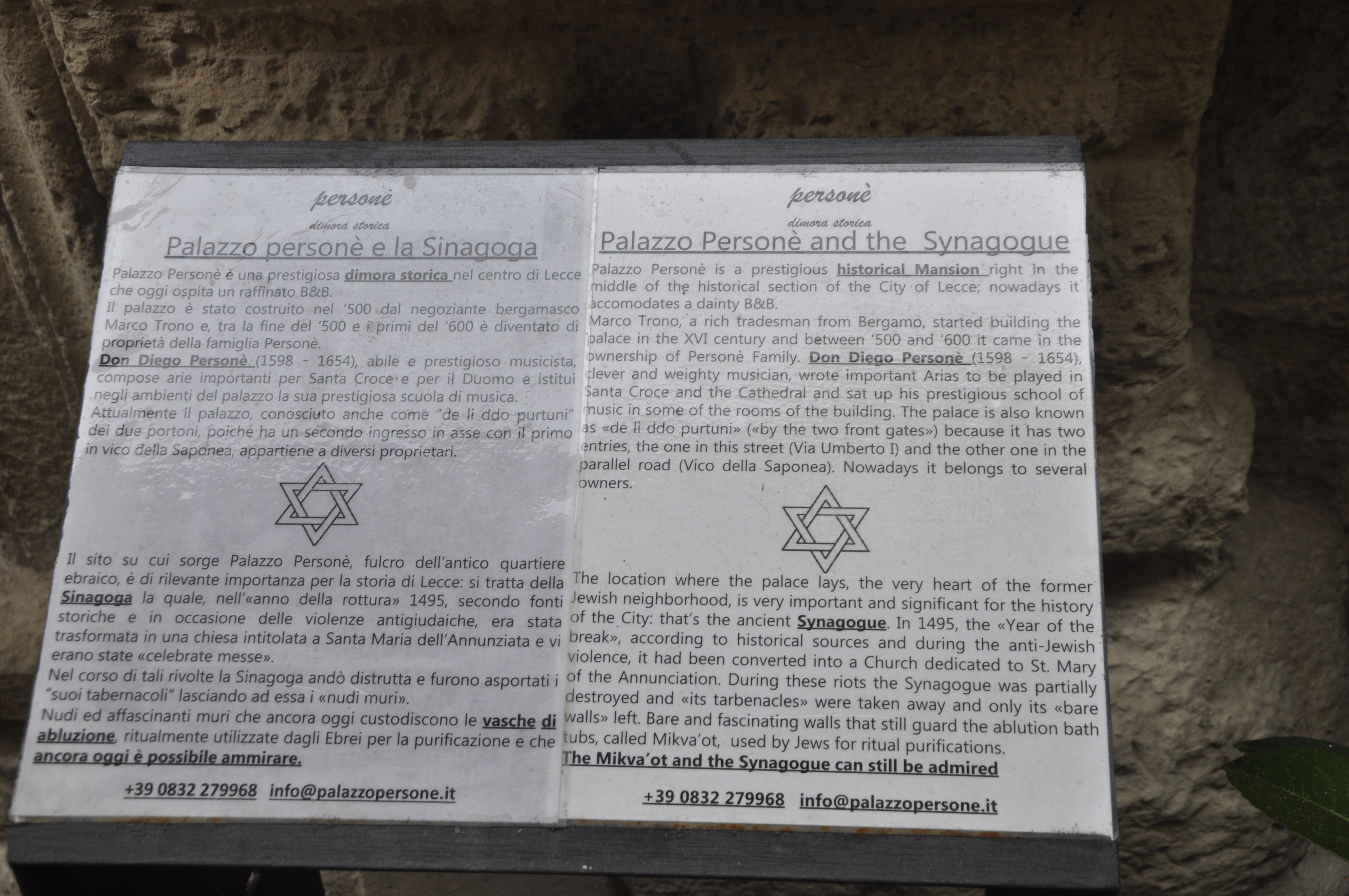

Walking across the piazza in front of the Church of Santa Croce, Giuseppe informed us that the market the Jewish community frequented lay beneath the stones. After making arrangements once again, he led us down a flight of steps through the glass doors of Persone Bistrot, a restaurant in a small portion of a large building. When the work began on the restaurant in 2003 they discovered two separate entrances and more mikvot basins along with channels for bringing in natural rainwater. At the time of the renovation, fresh water still flowed into the pools. Excavators determined that this marked the site of Lecce’s synagogue as described by the sign outside. In 1495 a mob set fire to the Jewish quarter and killed a great number its inhabitants. The synagogue was demolished and a church was erected on top of it. Later it became a warehouse and then was closed for centuries.

The restaurant designed Plexiglas floors so that visitors could look down and see the excavations. Giuseppe pointed to where a wall separated the women’s section from the men’s (hence the two separate entrances). No one knows how much of the large building covers other Jewish structures and it doesn’t appear that archaeologists will have an opportunity anytime soon to find out.

Giuseppe explained that the restaurant manager, Catarina, who had opened the space for us, was fascinated by Jewish history and had been collecting as much information as she could about the original purpose of the building and the lost Jewish community. She asked us if we wanted to see more in the back where only the employees were permitted. We readily agreed and she slipped us through the kitchen to a stone archway leading down some ancient steps. There we found more basins that were presumed to be where utensils were dipped to kasher (make kosher) them. I took a couple of quick pictures before Catarina nervously escorted us out.

Shaft to let fresh rain water into the mikvot

Later I learned that Catarina would have gotten into a lot of trouble if the owner of the restaurant had discovered that we gained access to the restricted area. Although Giuseppe had heard about the additional basins in the back, he’d never had the opportunity to see them. Once outside the restaurant, he implored me to send him the pictures because, as far as he knew, I was the only one with photographs of that area of the building. I was only too happy to comply with his wishes. I couldn’t think of a better way to show my appreciation for the time he took to show us these treasures. No one knows how much of the large building covers other Jewish structures and it doesn’t appear that archaeologists will have an opportunity anytime soon to find out.

Giuseppe led us down Via della Sinagoga and pointed out a bed and breakfast with a sign partially in Hebrew. The owner, Michelangelo, also owns the tobacco shop near the famous church of Santa Croce. For years he had been collecting all the oral legends of the neighborhood and was happy to share his affinity for Jewish history with the archaeologists when the excavations began. He explained that there was a very old tale that a Jewish cemetery lay along Via della Sinagoga. When he began converting an old building into a B&B along the street, he discovered ancient structures under his building. Unfortunately, the government authorities ordered him to seal it up and leave it unexplored. Based on Giuseppe’s description of the political climate of Lecce, I’m guessing that the Hebrew sign outside is a non-verbal protest against those in the community who do not want more Jewish sites uncovered.

Right next door to Michelangelo’s little hotel is building #8 on Via della Sinagoga. We learned that the community considered it cursed because of a long history of tragedy associated with the structure. For example, during the Fascist period, this location housed a fencing school and over a period of time, the footwork loosened the flooring. One day it collapsed and killed all of the fencers. A succession of owners have also met with tragic deaths. Recently the property was purchased once again and the new owner allowed Giuseppe to explore the site. He discovered successive layers of buildings under the street level. The lowest level included a basin of fresh water. If indeed this is the location of the ancient cemetery, Giuseppe speculates that this might have been the funeral house with a bath for the Jewish ritual of washing the dead before burial. Until the owner has the funds for renovation, excavations are on hold and the mystery of the cursed house on Via della Sinagoga will go unsolved. I hope all ends well for the new owner!

Though only a tiny portion of this area of Lecce has been excavated, the discoveries indicate a relatively large, well-established Jewish community lived here until 1495. There is evidence that Jews began to return to the port city in the 1800’s. Then once again during the Fascist era in the 20th century, the Jews of Lecce disappeared along with most of the Jews of Italy sent to the Nazi camps in northern Europe. Giuseppe doesn’t think any Jews live in the city even today.

I’ve been to the beautiful city of Lecce many times over the last two years, but this visit wins the prize for the most exciting. I write historical fiction but sometimes, real life adventures in history are just as dramatic and amazing.

I truly enjoyed your article! It depicts our little “Indiana Jones adventure” so well!

I am so happy we got to do this.

I hope your travels are going well and just to let you know… Of course I DIDN’T pick up my notebook yet! OYVEY!!!!

I love your blog… COMPLIMENTI! The way you write about your experiences and ideas makes me feel as though I too am a part of it all! Thank YOU!

Syd

Robin, love hearing about your fascinating adventures! Hope you write some more historical fiction based on these finds! All the best to you!

So wonderful hearing from you Consuelo. Glad you are enjoying my adventures. I’m moving back to Seattle in a few weeks. I’m going to miss all the old rocks of the old world! Hope all is well with you.

The Curse of #8 could be a great story–misfortunes befalling those associated with the building over the ancient Jewish cemetery and funeral house! Very Indiana Jones, indeed!

Sad that none of these historical sites are accessible and properly excavated.

Thank you for another fascinating post!

I’m glad you enjoyed hearing about my adventures. Perhaps in the future the town of Lecce will realize the potential of Jewish tourism!

Congratulations, Robin, on the most fascinating post I can recall reading thus far on the Internet!

I am trying to read the portion of the inscription that you photographed. Here is the transcription of the letters I can discern, along with translations as if they were in biblical Hebrew, instead of what they are more likely to be, which is medieval Hebrew:

From right to left:

)yn z[h?]by )[y?]m byt [h?] . . .

visually clear: )yn = “There is/are no ”

second letter not visually clear: z[h?]b. The Hebrew word zhb = “gold,” but I can’t explain the yodh following zhb. ?Possibly an abbreviated plural ending, from -iym to iy?

potential second letter not visually clear: )[y?]m.

)m = the preposition “with” or the adverbial conjunction “if.” The potential yodh as a second letter might simply make explicit the vowel i in the word )m .

visually clear: byt = house

According to your report above, “Giuseppe also showed us a stone inscribed with Hebrew which I believe said “bait le ohavei hael” (House for God Lovers).” Because the letter following beyt is cut in half by the edge of the photo, all I can do is speculate that the unseen portion of the inscription might read, following byt, with unwritten vowels inserted:

ha-)ohavey ha)el

So then, according to this imperfect transcription, completed with a speculative ending, the inscription might potentially be translated:

??? There are no gold [item]s with the house of those who love God. ???

Potential background for the first two words is that on epitaphs of ancient tombs, to discourage tomb-robbers, the words “There is no gold or silver inside” sometimes appear. Although this inscription does not seem to be related to a tomb, here this expression might be applied to a building that could potentially house items of monetary value to discourage theft.

This is as far as I can go in trying to understand the inscription. Welcome to imperfect, initial epigraphic study of a new inscription!

Correction (of course!):

My speculative ha-)ohavey ha)el should instead be: )ohavey ha)el.

The letter following the aleph could be the vowel holem, to express the o sound.

Also, to clarify “from right to left” at the end of the first paragraph of my first post above, the Hebrew inscription in the photo is of course written from right to left, but my transcription into English letters is written from left to right. Sorry for the confusion.

Oh wow, Robin, this is certainly one of your most exciting posts to date. Loved reading about your adventures around the Mediterranean! I completely agree with the person who suggested a story about #8 via della Sinagoga!

Thanks Bibi. It’s always nice to hear from you.

Everyone tells me this is my most exciting post. I don’t have adventures like this every day. How am I going to live up to my reader’s expectations now?

Hi,

Came across your post by chance. Fascinating! The inscription is from Genesis 29:17, from the Jacob’s words after his dream. It is part of this verse:

[How awesome is this place!] This is none other than the house of God; [this is the gate of heaven] – ]אין זה כי אם בית אל

It is a verse often found in synagogues.

Glad you found me. Thanks for the comment.

Thank you for posting this Robin. We were recently in Lecce and happened on Via della Sinigoga and saw the Hebrew inscription on the Michelangelo B&B sign and were very curious about the Jewish history of Lecce. Clearly a rich, fascinating and sad history with much still to be discovered. The B&B website states that they will provide a tour of the Jewish sites for their guests. We’ll certainly include that in a future trip to Puglia.

Thanks again.

Paul from Wolfe Island Ontario

Glad my post was useful for you and that you had a chance to see a bit of the old Jewish quarter.