Image credit

Image credit

“A handful of the choice flour and oil of the meal offering shall be taken from it … and this choice portion shall be turned into smoke on the altar as a pleasing odor to the Lord.” Leviticus 6:8-9 (JPS translation)

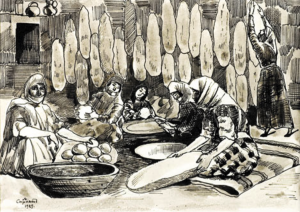

In ancient Israel bread baking was predominately a woman’s activity. Within the household economy, women performed all the tasks of bread making from grain to final product. Since bread consumption provided the highest calorie content of the ancient Israelite diet and therefore was the most important food staple, the role of the baker was held in high esteem and wielded economic power.

Bread played a significant role in the sacrificial system of the ancient Israelites as well. The baking of the special breads for the sanctuary became a highly skilled profession. “The preparation of this bread was so intricate that only one family, the Garmu, was deemed sufficiently expert in the art…” (Encyclopedia Judaica). Since the priests partook of the cereal offerings, the bread had to be ritually pure. Later when the Temple was built, the baking facilities were in the precincts of the Temple (Interpreters Dictionary of the Bible “Baking”; see also Ezek. 46:20, 23-24). From 1 Sam. 8:13 it appears that women retained the specialization as professional bakers within the royal palace. In 2 Kings 23:7 we learn that women weavers worked within the temple compound so it seems very likely that women were also among the skilled bakers employed in the Temple itself.

In this week’s reading we learn that the bakers who provided bread for the sanctuary were required to take a small amount of the dough and burn it so that it would make a “pleasing odor to the Lord.” This simple act turned the baking process into an act of prayer. Separation of the dough (hafrashat challah in Hebrew) has survived into modern times in observant Jewish households. Since the Temple no longer exists and priestly offerings cannot be made, the ritual is interpreted on a symbolic level. Like God gathering together the dust of the earth and mixing it with water to make a “dough” to create the first human, women mix and knead flour to create a sacred experience.

Rabbi Shoshana Gelfand teaches that, “The word for ‘sacrifice,’ korban, comes from the root k-r-b which means ‘to draw near.’ A sacrifice, therefore, is the means by which we draw near to God…” The ancient Israelites used bread, a common everyday item to create a bond between themselves and God so intimate they were united, an ‘I-Thou’ relationship to use the great Jewish philosopher Martin Buber’s term. Within the traditional Jewish community, contemporary women find it one of their greatest privileges to separate a small amount of the dough from their homemade challah bread and burn it in the oven. Perhaps they are preserving a ritual performed by women for thousands of years.

Finally I will leave you with one of my favorite stories about women and bread in the Bible. Abigail, one of the most clever women in literature, was married to a wealthy man named Nabal (literally, “fool”). When David (the future king of Israel) and his men, approached Nabal at the end of the sheep-sheering season to collect their wages for protecting Nabal’s flock, Abigail’s husband refused to pay them. David vowed to destroy Nabal and all his household. Gathering together 200 loaves of bread, wine, dressed sheep, roasted grain, raisin and fig cakes, Abigail intercepted David. She offered the bread, wine and meat to appease the future king. With a carefully crafted speech and the extravagant food, she prevented a massacre. After Nabal’s death, King David married Abigail and she lived the remainder of her days in the king’s palace in Jerusalem. In honor of Abigail’s peacemaking, it is customary, even to this day, to make raisin-filled challah bread, particularly on the Jewish new year, Rosh Hashanah.

For the full story, see 1 Samuel 25:14-25. Regarding the connection with raisin challah, Abigail.

Further Reading

Gelfand, Shoshana – “Vayikra: The Book of Relationships” in The Women’s Torah Commentary, Elyse Goldstein and Andrea L. Weiss, eds. (URJ Press, 2007)

Meyers, Carol – “From Field Crop to Food: Attributing Gender and Meaning to Bread Production in Iron Age Israel,” in The Archaeology of Difference: Gender, Ethnicity, Class, and the ‘Other’ in Antiquity: Studies in Honor of Eric M. Meyers, D.R. Edwards and C.T. McCollough, eds. (Boston: American Schools of Oriental Research, 2007) 67-83.

Meyers, Carol – “Having Their Space and Eating There Too: Bread Production and Female Power in Ancient Israelite Households,” Nashim: A Journal of Jewish Women’s Studies 5 (2002): 14-44.

One thought on “Of Bread and Raisin Cakes”

Comments are closed.