I want to very briefly introduce you to three biblical women we hear very little about: Anna, Sarah and Deborah. No, not the prophetess that blessed Jesus, the wife of Abraham or the judge of Israel. I’m talking about three women from a piece of ancient Jewish literature, The Book of Tobit, part of the Catholic canon. Fragments of Tobit were found with the Dead Sea Scrolls, an indication that the book was circulated among Jewish readers in the second century BCE. The fantastical story relates the adventures of the Israelite Tobit raised by his grandmother Deborah who taught him the Law of Moses. When Tobit went blind, his wife Hannah supported the family as a seamstress. As the narrative progresses, we meet Tobit’s daughter-in-law, Sarah, who sought out God in the depths of her despair after seven unsuccessful marriages. Although Tobit is by no means a feminist textbook, its portrayal of non-traditional gender roles make for an interesting read. Since some of the characters of Tobit are also characters in my novel Judith: The Wise Woman of Bethulia, I’ve studied the text in the past. Recently, the story leaped back into my life. Let me explain.

My sister and I woke up one morning last fall in Amman, Jordan with the intention of finding the site where archaeologists believe John the Baptist preached and practiced the immersions for which he received his nick name. Prior to the trip, I’d spend hours online trying to get driving instructions via Google Maps but always came up empty handed. It seemed there were no roads that connected point A to point B. But the baptismal site is considered one of the biggest tourist attractions in Jordan. There had to be signs pointing the way, right? So with a very sketchy and small map from the hotel, Shawna and I started driving in the right direction. Oh, did I mention that the GPS in the rental car stopped working?

An hour or two later Shawna and I came to a screeching halt at the end of a dirt road, having exhausted all the other roads heading west out of Amman. Now what? I just stared out the front of the car with no clue where to go next. Our only option seemed to be to return all the way back to Amman and start over again. That would break a deeply held family rule against backtracking. An adventurous person does not go back the way she or he came. It’s just not done.

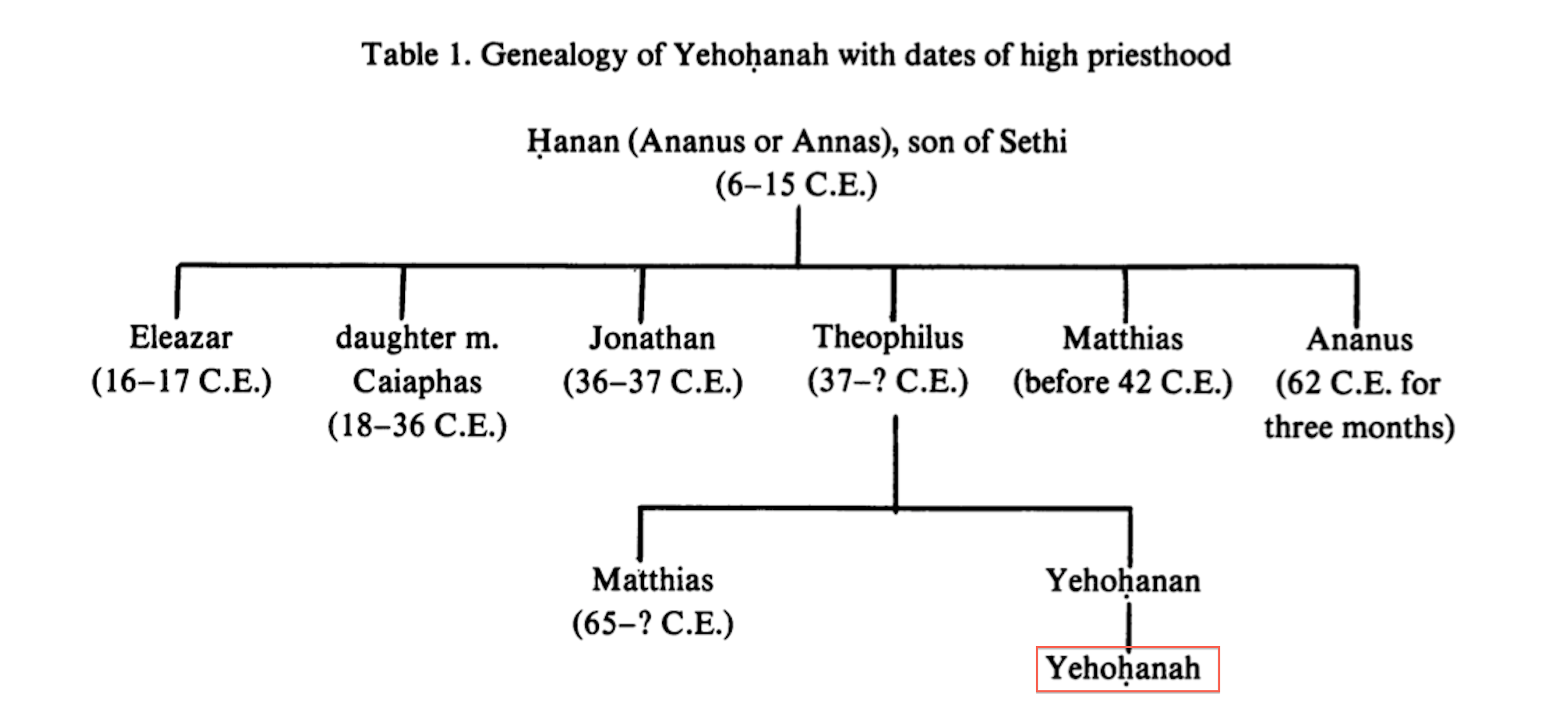

Then I finally looked at the sign at the end of the road and read the word “Tobiad.” “I know where we are!” I shouted while rummaging through my notes. “We are in the Land of Tob!” My sister, who is not a bible freak like me did not share my excitement. This bit of information did not impress her in the least. Undaunted I continued, “This could be the remains of the town of Thisbe from the Book of Tobit.” There are a variety of guesses about the location of the biblical Land of Tob mentioned in Judges 11:3-11 but generally it is agreed that it is in the region of the Ammonite kingdom, present day Jordan. It was the ancestral territory of the Tobiad family of Judean nobles who had strong political connections with the Judean royalty. The main characters of The Book of Tobit were members of this distinctive family.

I pulled out my typed notes I’d prepared and brought with me on the off chance that we could somehow squeeze in just one more biblical site to our jam-packed schedule. Shawna stared at me, incredulous that I knew the history of our accidental destination. Then she started laughing at me. I think I joined her. After we calmed down, I read what I’d written:

“The small but impressive Qasr al-Abad, west of Amman, is one of the very few examples of pre-Roman construction in Jordan. Mystery surrounds the palace, and even its precise age isn’t known, though most scholars believe that Hyrcanus of the powerful Jewish Tobiad family built it sometime between 187 and 175 BCE as a villa or fortified palace. Although never completed, much of the palace has been reconstructed, and remains an impressive site. The palace was built from some of the biggest blocks of any ancient structure in the Middle East – the largest is 7m by 3m. The blocks were, however, only 20cm or so thick, making the whole edifice quite flimsy, and susceptible to the earthquake that flattened it in CE 362. Today, the setting and the animal carvings on the exterior walls are the highlights. Look for the carved panther fountain on the ground floor, the eroded eagles on the corners and the lioness with cubs on the upper story of the back side.”

My notes mentioned I should ask the gatekeeper to open the interior. Until that moment, Shawna and I had been the only people around but suddenly a man appeared. We had to assume he was the aforementioned gatekeeper. With hand gestures and big smiles he unlocked the gate and we stepped into the ruins of the massive palace. We spent a good 45 minutes exploring and upon exiting we thanked the gatekeeper. Just then the call to prayer sounded. The time had arrived for the site to be shut down for Friday afternoon services. It wouldn’t be opened again for several days. We had found the Land of Tob just in time.

By the way, we ended up returning to Amman and eventually found the baptismal site. It was worth breaking family tradition.

For Further Reading

You can find The Book of Tob online here.

Eskenazi, T. – “Tobiah” Anchor Bible Dictionary (Doubleday, 1992)

Gera, Dov – “On the Credibility of the History of the Tobiads” in Greece and Rome in Eretz Israel: Collected Essays, Aryeh Kasher, ed. (Yad Izhak Ben-Zvi, 1990)

Goldstein, J.A. – “The Tales of the Tobiads” in Christianity, Judaism and Other Greco-Roman Cults, J. Neusner, ed. (Brill, 1975)

Ji, C.C. – “A New Look at the Tobiads in ‘Iraq Al’Amir” LA 48 (1998); http://www.christusrex.org/www1/ofm/sbf/Books/LA48/48417CCJ.pdf

Mazar, Benjamin – “The Tobiads” Israel Exploration Journal 7 (1957) 137-147.

McCown, C.C. – “The ‘Araq el-Emir and the Tobiads” Biblical Archaeologist (1957,3) 63-76.

Miller, Geoffrey David – Marriage in the Book of Tobit (Walter de Gruyter, 2011)

Porter, Adam – “What Sort of Jews were the Tobiads?” in The Archaeology of Difference: Gender, Ethnicity, Class, and the ‘Other’ in Antiquity: Studies in Honor of Eric M. Meyers, D.R. Edwards and C.T. McCollough, eds. (Boston: American Schools of Oriental Research, 2007) 141-150.

Spiro, Abram – Samaritans, Tobiads, and Judahites in Pseudo-Philo: use and abuse of the Bible by polemicists and doctrinaires (New York : American Academy for Jewish Research, 1951)

Eskenazi, T. – “Tobiah” Anchor Bible Dictionary (Doubleday, 1992)

Gera, Dov – “On the Credibility of the History of the Tobiads” in Greece and Rome in Eretz Israel: Collected Essays, Aryeh Kasher, ed. (Yad Izhak Ben-Zvi, 1990)

Goldstein, J.A. – “The Tales of the Tobiads” in Christianity, Judaism and Other Greco-Roman Cults, J. Neusner, ed. (Brill, 1975)

Ji, C.C. – “A New Look at the Tobiads in ‘Iraq Al’Amir” LA 48 (1998); http://www.christusrex.org/www1/ofm/sbf/Books/LA48/48417CCJ.pdf

Mazar, Benjamin – “The Tobiads” Israel Exploration Journal 7 (1957) 137-147.

McCown, C.C. – “The ‘Araq el-Emir and the Tobiads” Biblical Archaeologist (1957,3) 63-76.

Miller, Geoffrey David – Marriage in the Book of Tobit (Walter de Gruyter, 2011)

Porter, Adam – “What Sort of Jews were the Tobiads?” in The Archaeology of Difference: Gender, Ethnicity, Class, and the ‘Other’ in Antiquity: Studies in Honor of Eric M. Meyers, D.R. Edwards and C.T. McCollough, eds. (Boston: American Schools of Oriental Research, 2007) 141-150.

Spiro, Abram – Samaritans, Tobiads, and Judahites in Pseudo-Philo: use and abuse of the Bible by polemicists and doctrinaires (New York : American Academy for Jewish Research, 1951)